Buying the dip: is there ever a "Black Friday" in investing?

"Buy the dip" is a favorite strategy for too many investors. But let's look at what the data actually tells us.

What do these quotes have in common?

“Buy when there's blood in the streets, even if the blood is your own” – 19th century Baron Rothschild

“Whether we're talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.” – Warren Buffett

“The stock market is too expensive; I will wait for a dip to buy it.” – most of my friends this year.

They’re all talking about bringing the Black Friday or Cyber Monday mindset to the stock market. It’s tempting to go find stocks that are on sale. And there are always the stories of great investors who bought and sold at just the right time.

But let’s see if buying the dip actually works – and if it does, how to implement it as a strategy.

Buying the dip fails more often than you think

Nick Maggiulli (he writes Of Dollars And Data, a great blog if you like to look at investing from a data point of view) ran the numbers on buying the dip.

He compared the returns from dollar-cost averaging (DCA) and buying the dip (BTD) for every 20-year period between 1920 and 2000.

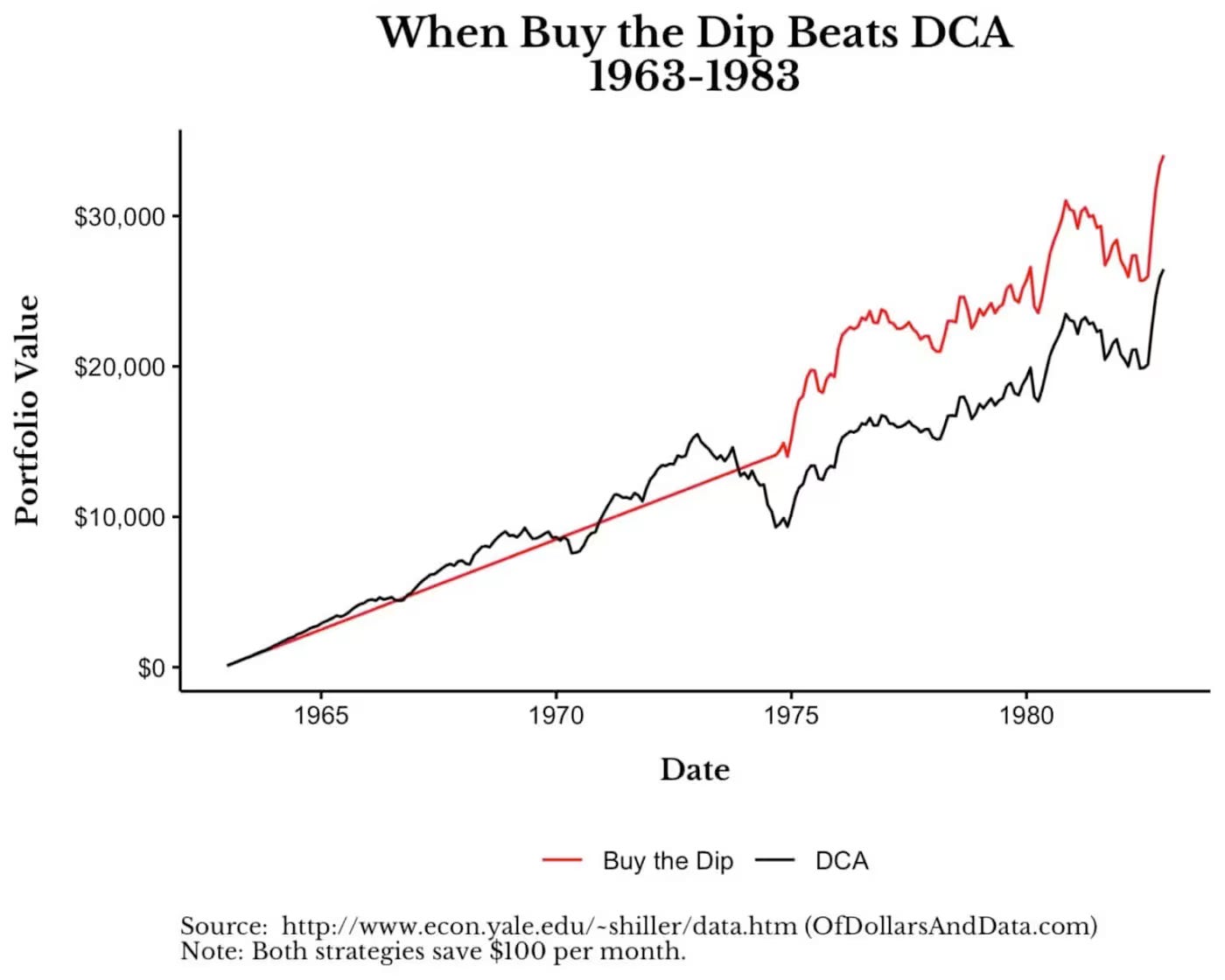

For BTD, its best performance relative to DCA happened between 1963 and 1983. Here BTD beat DCA by 29% in total:

But this turns out to be just one isolated example.

Unfortunately, it turns out that most of the time Buy the Dip did very poorly.

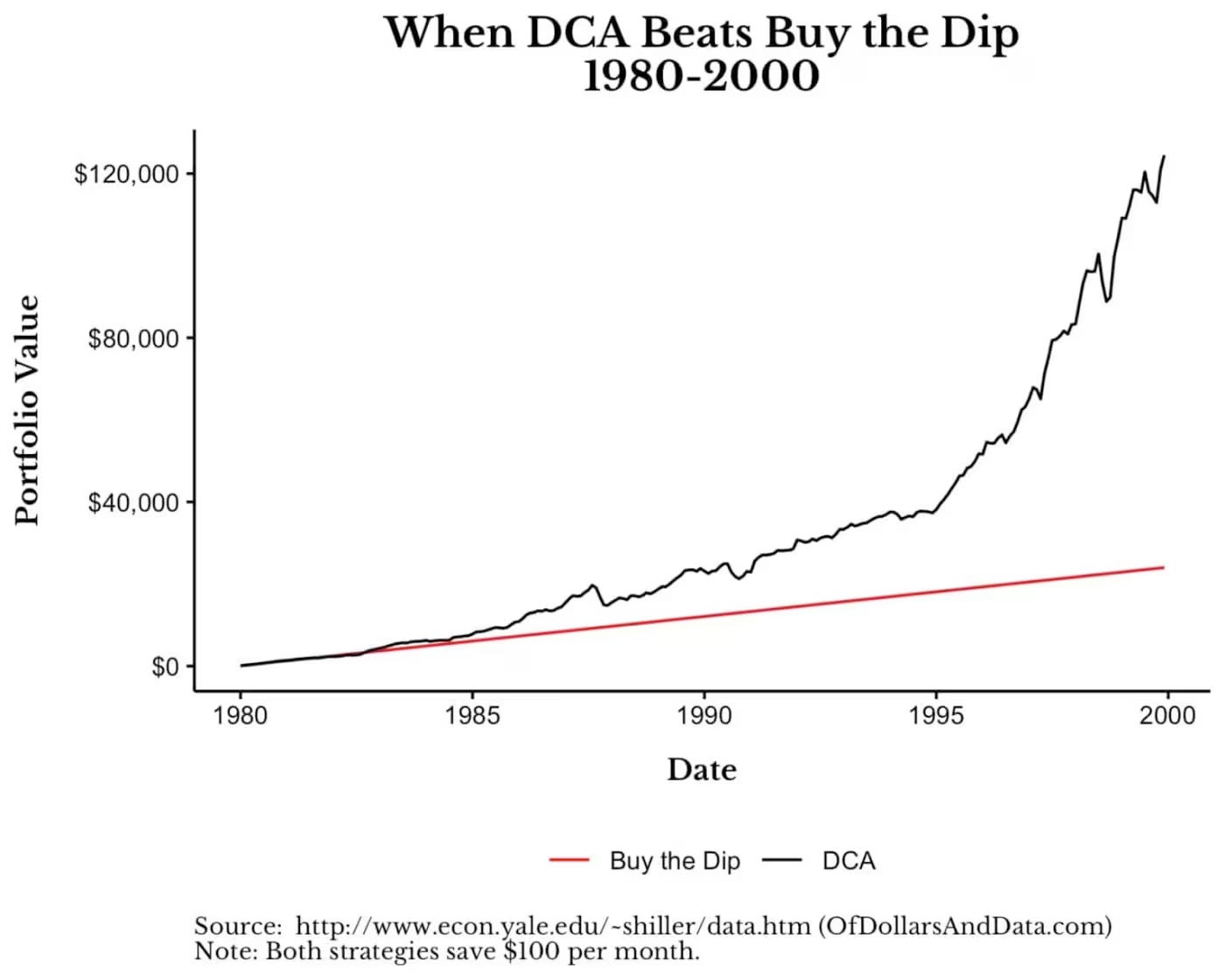

For example, if you would have chosen to only buy dips bigger than 50%, you would have sat in cash for the entire 20 years between 1980 and 2000, while the market left you in the dust:

There were no 50% dips at all during this time period.

As a result, Buy the Dip never gets invested. And because it never gets invested, DCA ends up beating it by 5x.

20 years later saving $100 per month would have turned into $120,000 if you dollar cost averaged, but only $24,000 if you waited to buy big dips only.

Now, this is an extreme example, but it does show what the main issue with Buy the Dip is: it sits in cash for too long. Meanwhile the market keeps going up.

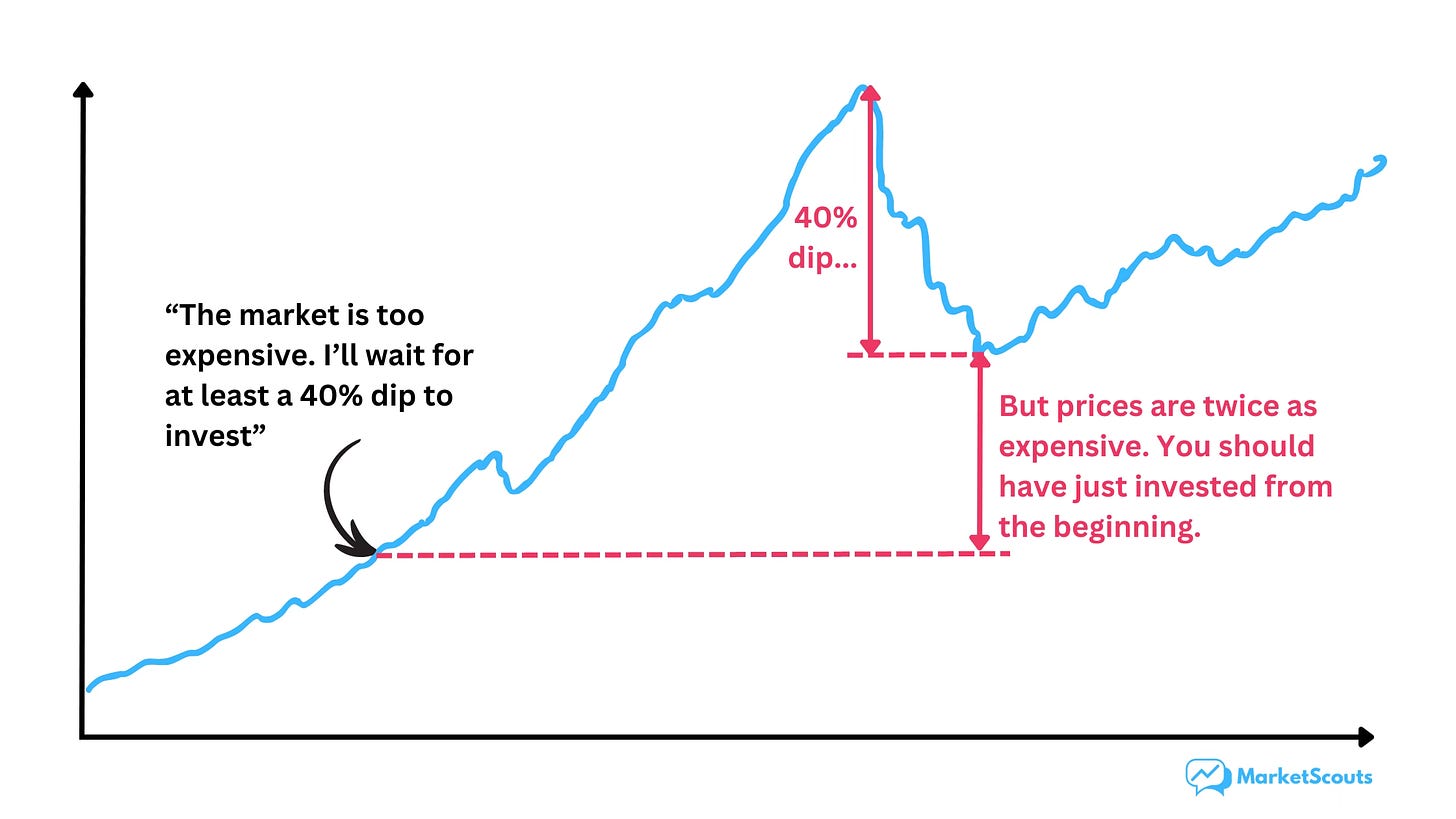

So when a dip occurs in the future, instead of buying on a discount you end up buying at much higher prices than if you just bought from the beginning.

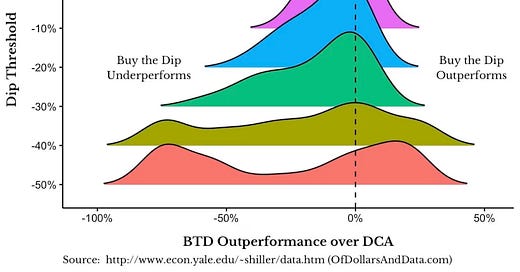

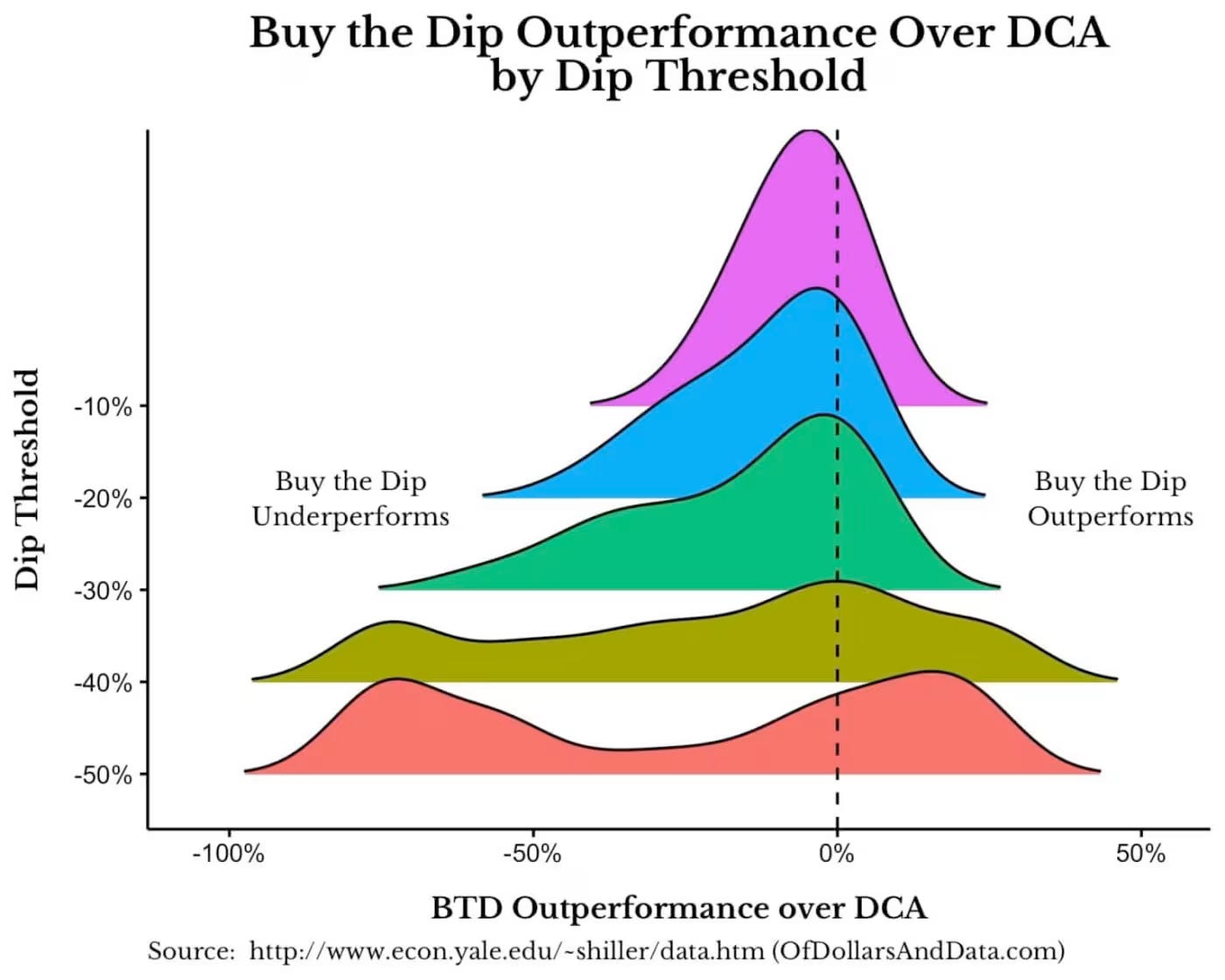

But I mentioned that Nick ran simulations for buying the dip every year, and for each dip threshold.

In most years buy the dip loses to DCA – much more often than it wins.

This chart might be a bit hard to read if you’re not used to charts like it, so let me translate it:

the size of those “hills” is how often BTD beats DCA; it’s a distribution of results.

as the dip threshold (your “target dip”) gets bigger, the hills flattens with the middle of the distribution moving left. This means that you get more negative results, on average. In other words, when your dip threshold increases, the outperformance is more extreme, but the underperformance is also more extreme as well.

so if you get lucky and catch a large dip, it’s worth it. But if you don’t get lucky, you’re losing on all the gains that DCA brings.

As Nick says: “when Buy the Dip wins, it tends to win by a little, but when it loses, it can lose by a lot.”

But obviously market crashes happen.

Obviously we’ve all watched “The Big Short”.

So what to do when we see a crash that screams “buy”?

How do make Buy The Dip work for you

Buy the Dip as your only strategy won’t work. I hope Nick Maggiulli’s charts convinced you.

But there are ways to make sure that you can take maximum advantage of dips if and when they happen:

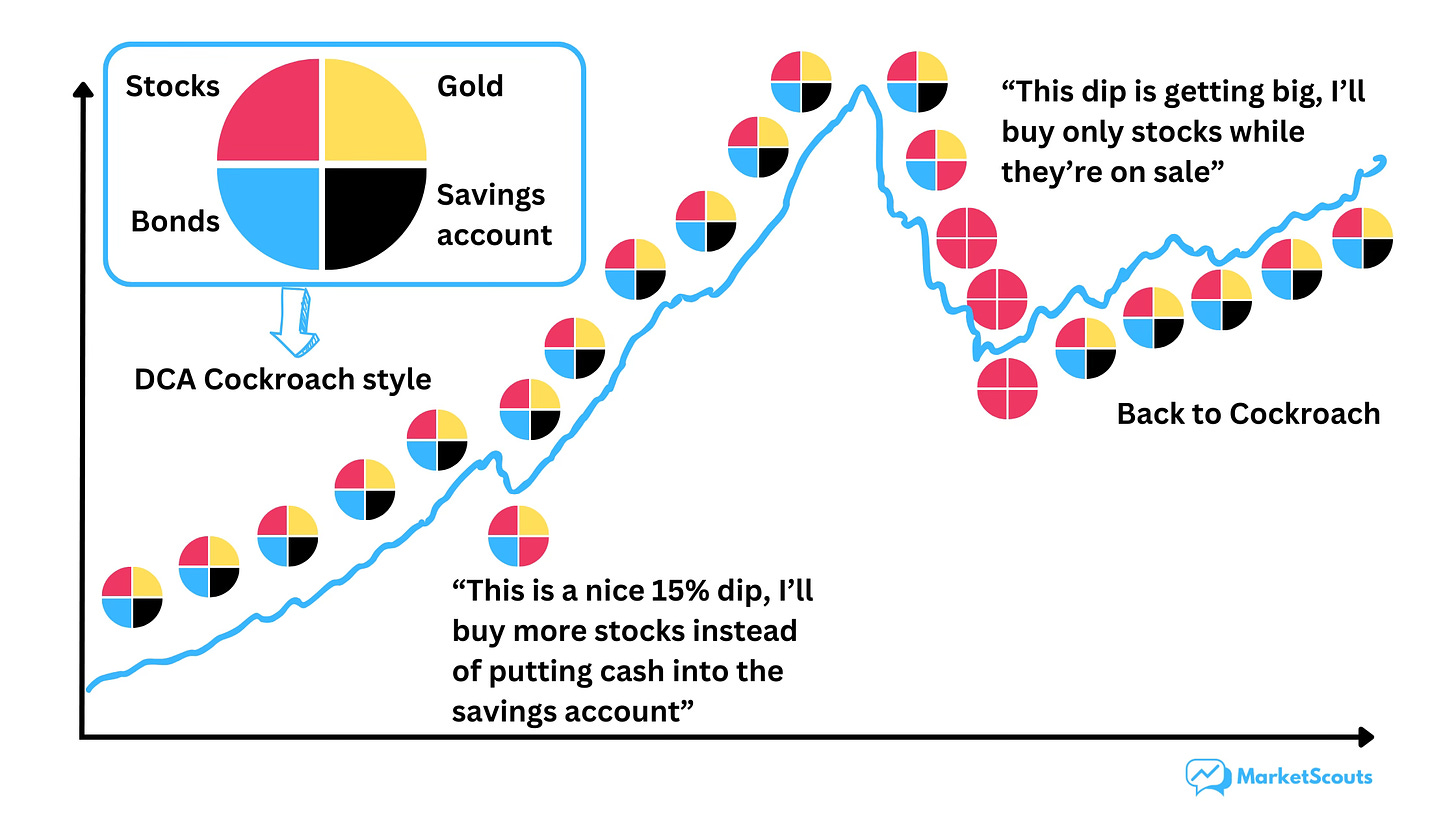

1. Combine it with DCA

This works best if you’re not 100% invested in stocks all the time, and are dollar-cost averaging into a mixed portfolio like the Cockroach Portfolio, which we talked about a few weeks ago.

The Cockroach Portfolio has 25% in stocks, 25% in bonds, 25% in cash, and 25% in gold.

If you feel really strongly about the dip, you could maybe go 100% into stocks that month. But only that month – don’t go breaking your own rules.

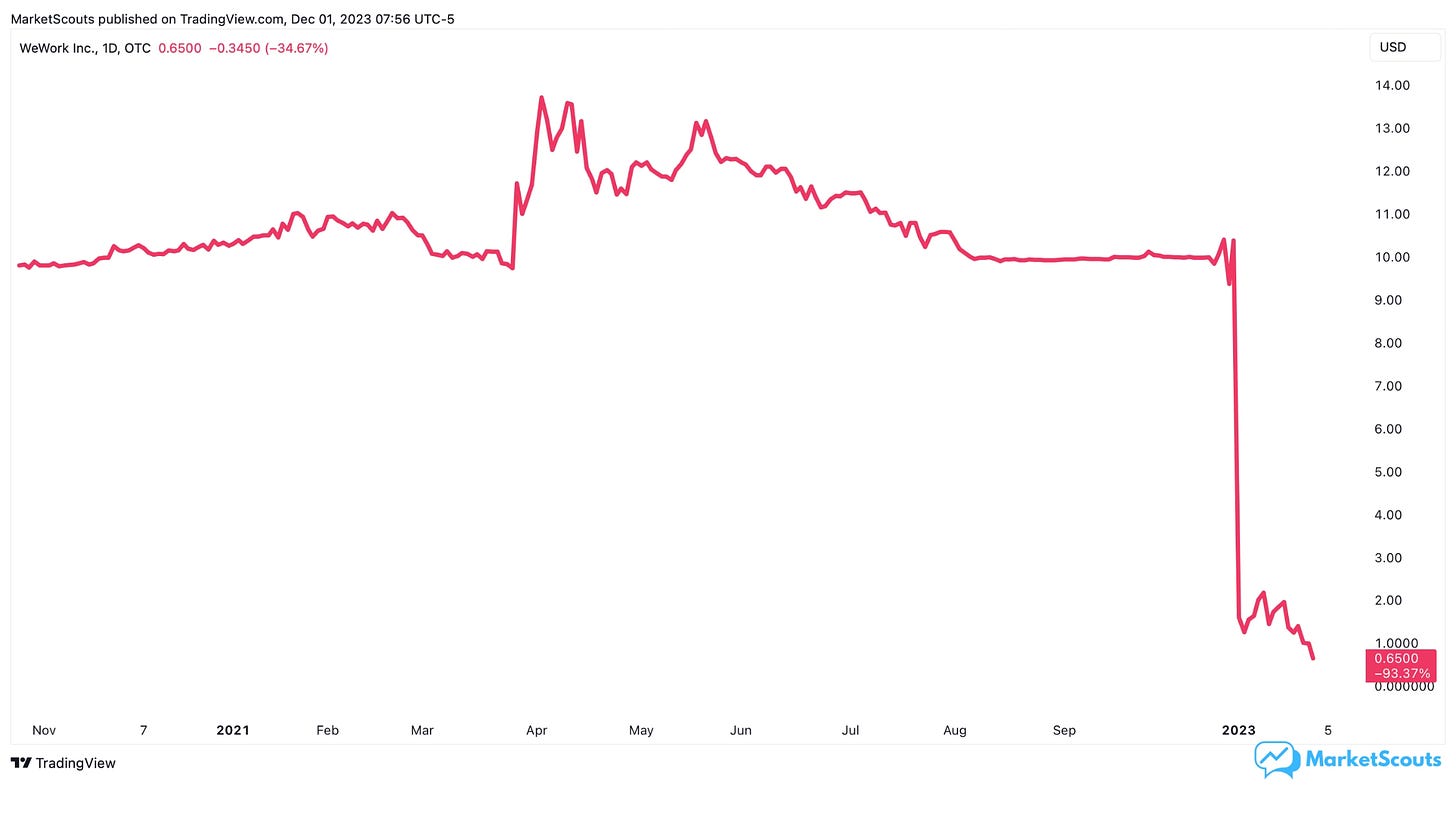

2. Think twice about buying dips in individual stocks

It is possible to find great companies that are caught up in a marketwide rout. Sure. And that’s especially true in a bear market. Stocks sell off even on good news then.

But usually a fall in price happens because there is something bad in the fundamentals of the business.

Unlike for Black Friday, a stock going on sale isn’t always a good thing.

The market isn’t stupid – it’s just afraid of something you don’t know. We’ve talked before about how buying companies that nobody won’t touch can be very profitable, but the risk is also very high.

A dip for a stock can easily turn into a cliff. Just look at what happened to WeWork recently.

3. Use big, market-wise dips as a chance to reconsider your strategy

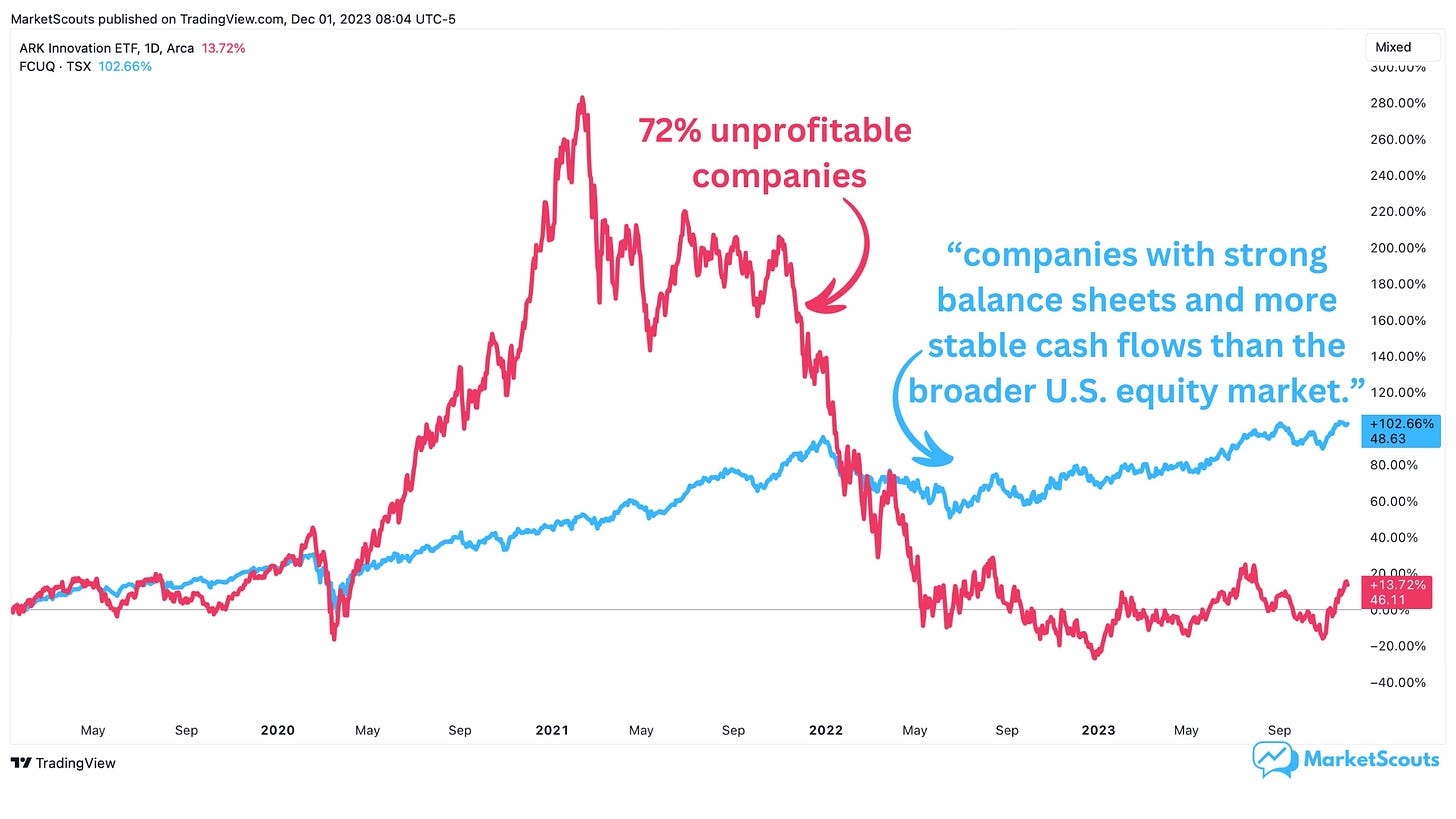

Buying the dip leads many investors to make a common mistake: piling back into the winners from the previous cycle.

But you should keep in mind two things:

first, the sectors that lead in the new cycle won't be the same as those that led in the previous cycle.

This is especially true when coming off a large bubble, like the 2020-21 in tech stocks. Instead of accepting the new reality, many investors see the dips as opportunities to buy back at a lower price.

But that’s not how bubbles work: once they pop, those stocks don’t return to being great investments in just six months or something.

So in the same example, instead of buying back unprofitable tech companies in 2022, investors should have looked at high-quality companies with stable cash flows and strong balance sheets.

Just look at how ARK Innovation ETF (which invested mostly in unprofitable tech companies) fared versus the Fidelity U.S. High Quality ETF, which pretty much invested in the opposite:

4. Whatever you do, don’t sit on cash.

If you have a lump of cash right now, just invest all of it instead of buying the dip, and also instead of spreading it out and dollar-cost averaging.

Dollar-cost averaging is meant for people who earn income monthly and they can only put invest a little bit on payday.

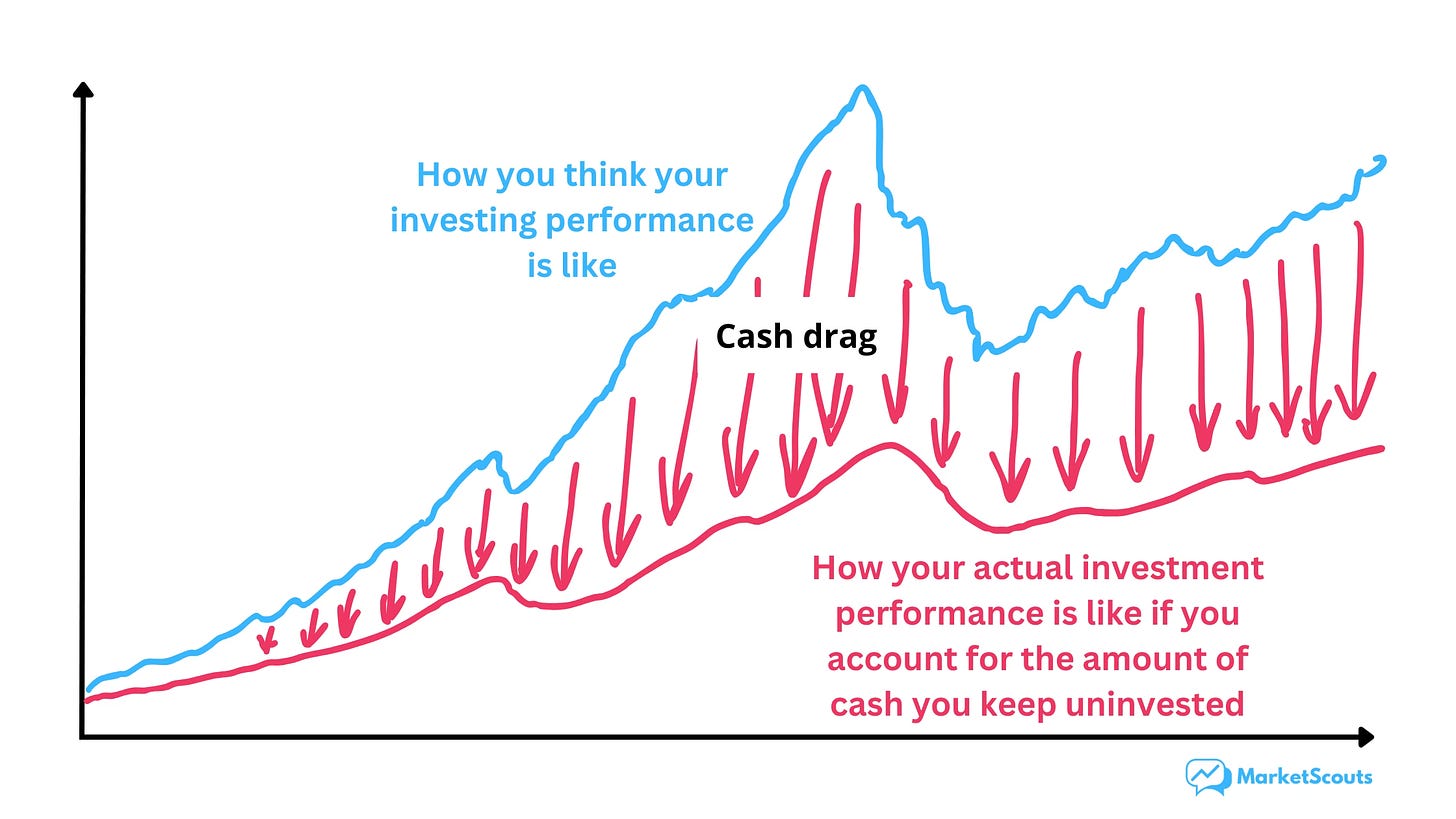

But when you try to dollar-cost average an existing large amount of money, you get slowed down by cash drag.

What is cash drag?

Let's say you have $10,000 available to invest. You decide to put 70% in the SPY ETF and keep 30% in cash. Over the next year, SPY gains 5%.

You made 0.7*5 + 0.3*0 = 3.5%.

Basically, cash is still a piece of your overall investment portfolio, but one that returns a nice juicy zero.

So when the market goes up, whatever cash you have creates a “drag” on your portfolio.

But that’s not all.

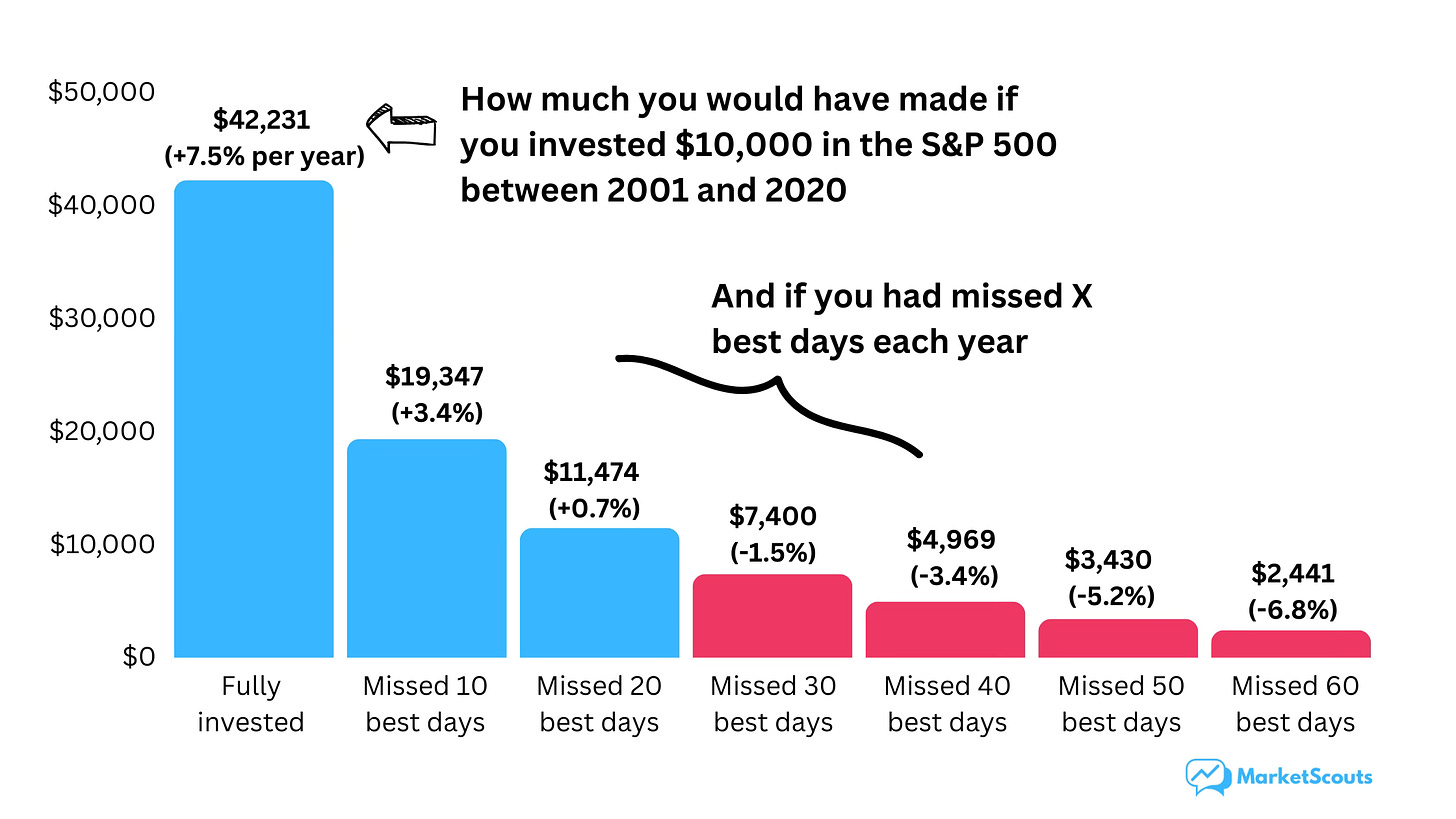

Between 2001 and 2020, seven of the best days in the market occurred within two weeks of the worst ten days.

And if you missed those by staying in cash and hoping for a bigger dip, you would have made half of what staying invested would have gained you.

And much worse if you missed more of the best days.

5. Maybe unsubscribe from most finance media (Bloomberg, WSJ, etc)

Obviously I have an incentive here. The MarketScouts motto is “no news, no noise, no jargon”.

But you don’t need to take my word for it. Staying away from news is actually a good strategy.

A study found that investors who checked investment updates frequently did worse than those who did it more rarely.

The investors who didn’t have access to daily account updates were able to invest in 33% in volatile assets and earn 54% more profits by doing so.

That's because investors who ignore the daily, weekly, or monthly ups and downs of their accounts are more likely to stick with their strategy and are not in that constant “fight or flight” panic mode.

You won’t be tempted to wait for dips (“I’ll buy when WSJ is panicking”) nor panic sell at a loss (“The WSJ is panicking, oh no!”).

Maybe there’s a reason why Warren Buffett’s office is so far from Wall Street and its noise.

If you’re still not convinced to stop waiting for dips

I hope this post convinced you to not keep your savings in cash, waiting for the day when “the big one” comes knocking.

But just in case, here are my closing arguments:

First, your dip may never come – while you’re missing out on years of compounded growth.

Second, even if it comes, you might not have the courage to act on it. As Morgan Housel said in his latest book, Same as Ever:

“If I, today, imagine how I’d respond to stocks falling 30 percent, I picture a world where everything is like it is today except stock valuations, which are 30 percent cheaper.

But that’s not how the world works. Downturns don’t happen in isolation.

The reason stocks might fall 30 percent is because big groups of people, companies, and politicians screwed something up, and their screwups might sap my confidence in our ability to recover.”

By the way, you can read a summary of Same as Ever in our previous post.

Finally, even if you do catch a dip and execute it perfectly, buying at the lowest low and then selling at the highest high, you’re still very unlikely to consistently beat someone who simply dollar-cost averages every month.

Don’t take my word for it, check out Nick Maggiulli’s more extreme example, Even God Couldn’t Beat Dollar-Cost Averaging.

He runs the numbers on buying the dip again, but assuming that you buy the lowest low and sell the highest high. And it still doesn’t work.

To quote Nick:

“Because if God can’t beat dollar cost averaging, what chance do you have?”

If you enjoyed this post, please leave a comment. I would love to know what your experience buying the dip is. Ever pulled off a really good trade like that?

Love your writing style and how you back it up consistently with data. Looking forward to your future posts.

I would like to study more on this topic. It's very debatable in my head. Loved it btw