Deep trash investing > value investing?

"Trashy" companies – which the market seems to give away almost for free – might be a better investment than just undervalued quality stocks. Here's why and how to find them.

What value investing is – and why it works

You often hear of “value investing”. The usual definition is something like “buying companies for less than they’re truly worth”.

It all started with Benjamin Graham, who believed that securities like stocks had an intrinsic value, different from their market price.

In 1932, Graham pointed out that, of the 600 companies trading on the stock market at the time, 200 of them traded for less than their liquidation value – how much you get if you sell a company “for parts”. In fact, many traded at a value less than how much cash they had in the bank.

Value investing has come a long way since. For example, now value investors focus more on a company’s future cashflow, discounting that to the present – which is why interest rates are so important in investing.

Value investing has been so popular for so long because many studies show that if you sort companies by PE (price to earnings), PB (price to book), and PCF (price to cashflows), the “cheapest” ones tend to do much better over the long run.

But “cheap” isn’t quite the right word: “discount versus intrinsic value” is better.

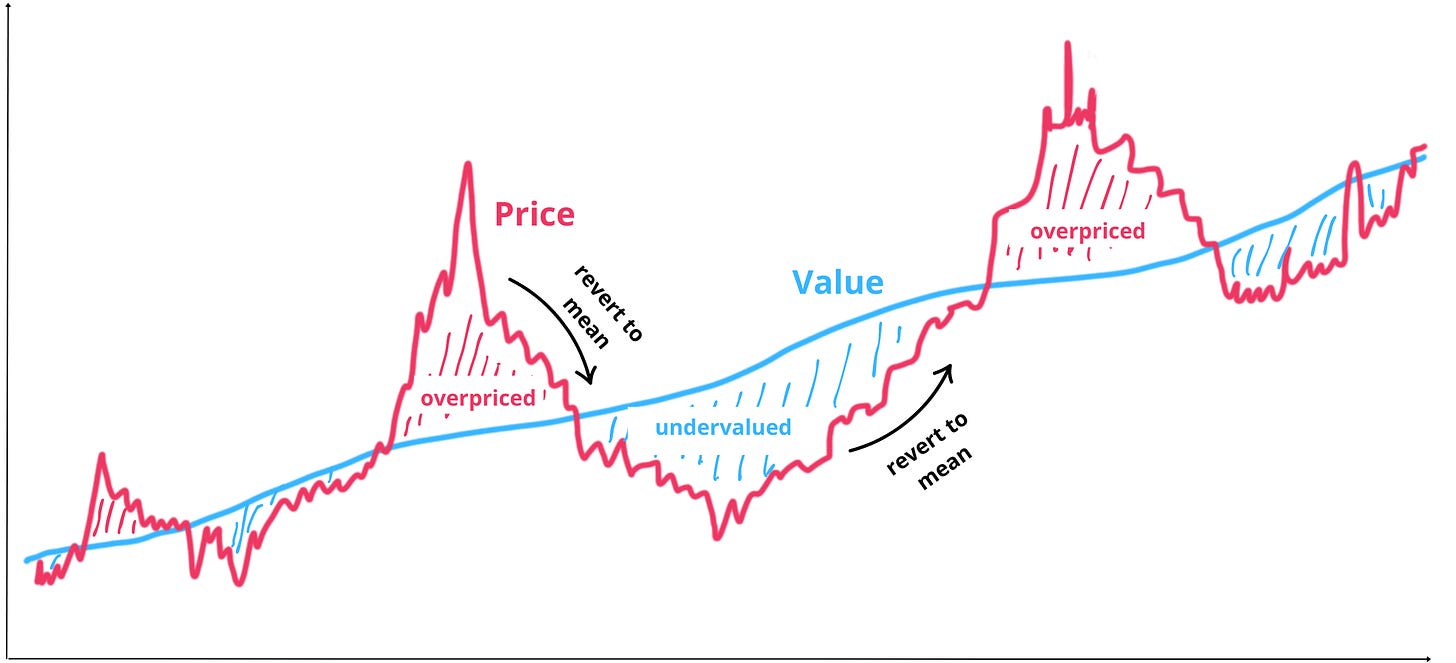

Which is why another way to look at value investing is “buying a company under its mean value and waiting for it to revert to that mean”.

That’s because price tends to fluctuate way more than intrinsic value. Eventually (and this can take years), as the market prices in news, financial reports, etc, it reverts to the intrinsic value.

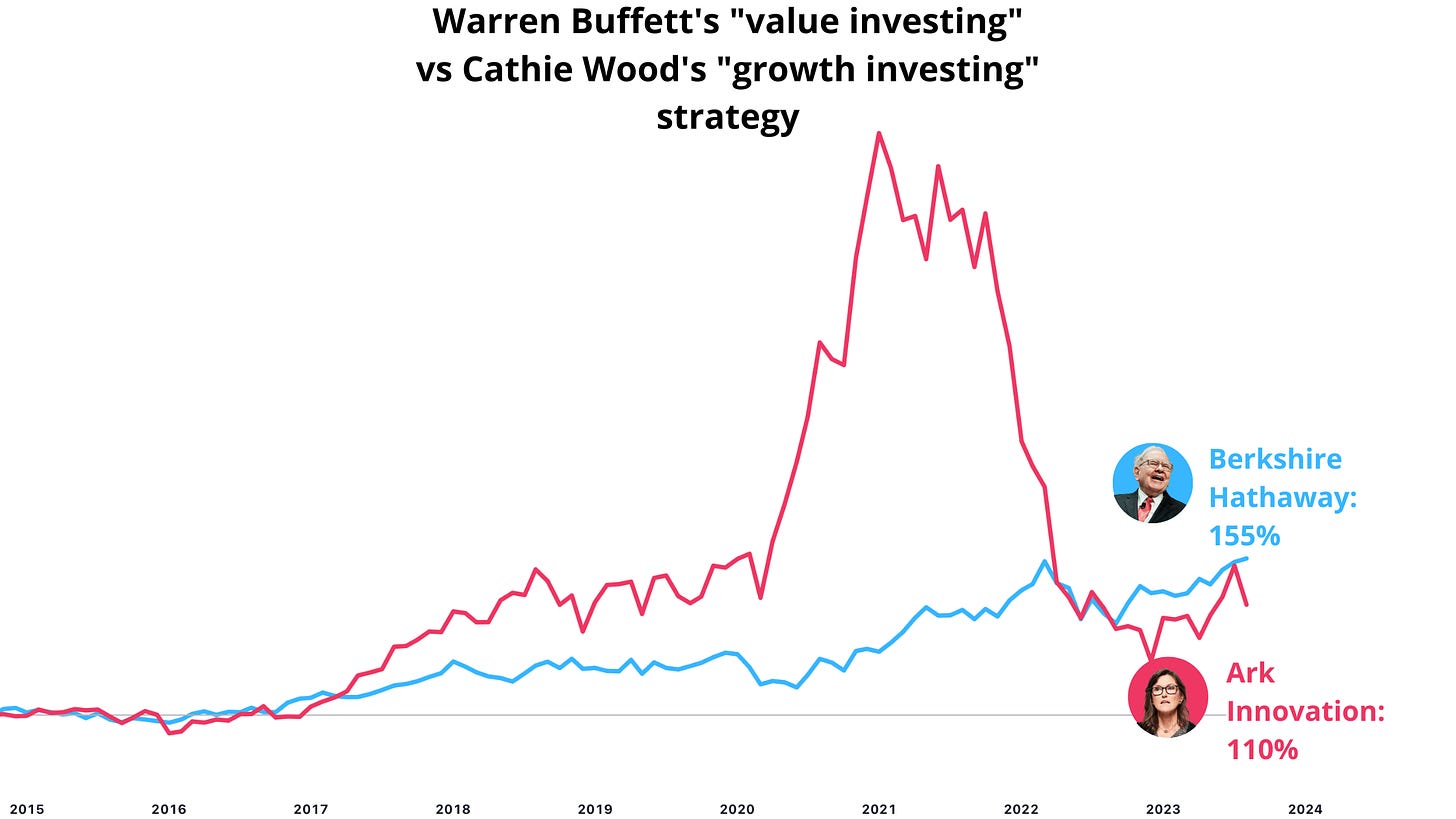

This might sound theoretical, so here’s a real life example of how value investing can beat other strategies over the long term:

What’s a “deep trash play”?

A “quality” undervalued company has a good balance sheet (low levels of debt), consistent earnings, predictable future cash flow, and actual growth.

In contrast, a deep trash play basically means investing in a company that’s… too cheap. And not just too cheap, but too cheap for obvious and worrying reasons:

it’s not making a profit (earnings)

or earnings do exist but are not enough to pay its high levels of debt

and maybe in a declining industry facing tons of competition from new technologies.

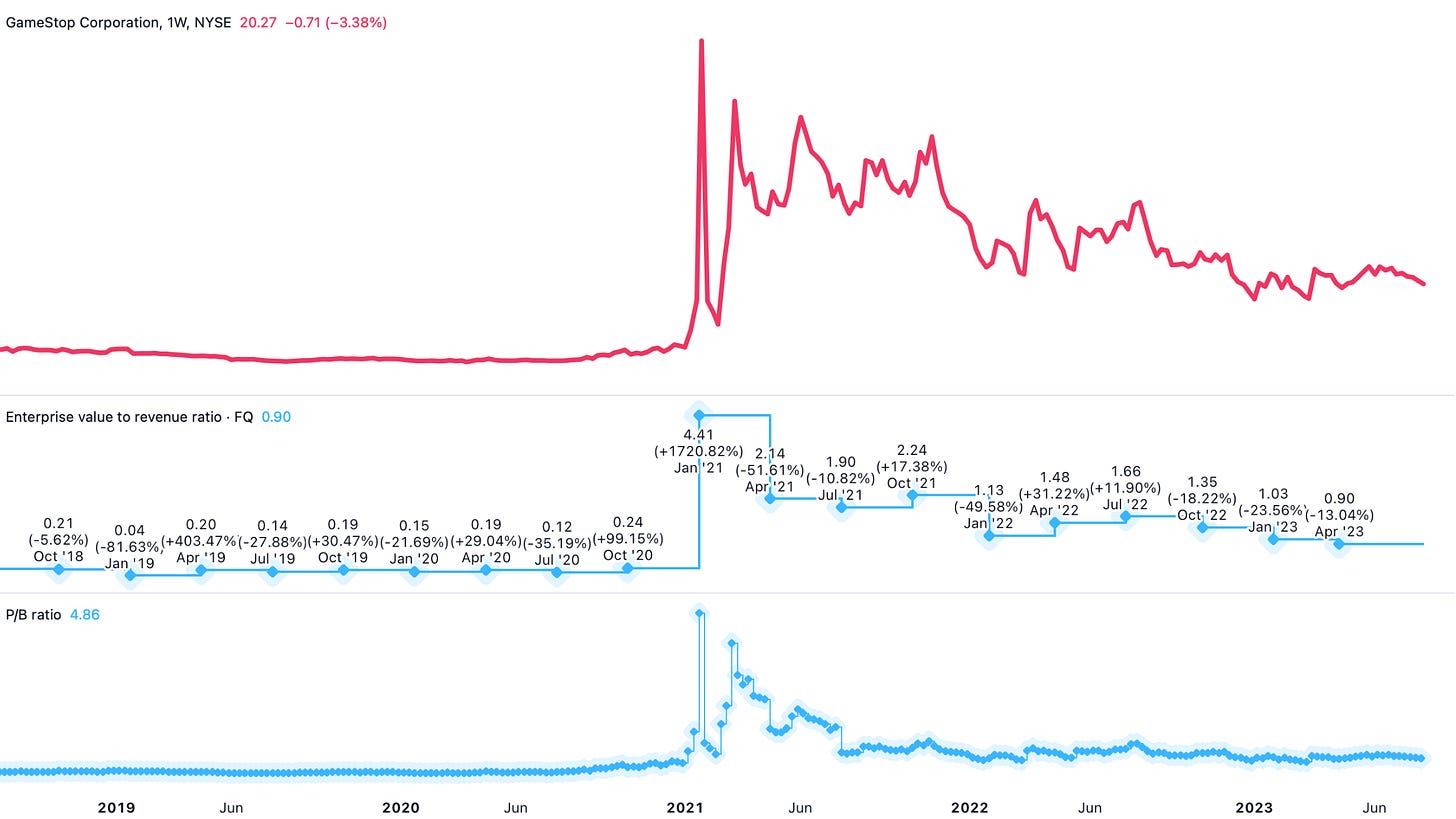

A recent example: GameStop.

A company with a dying business model (selling physical copies of video games in physical stores, during Covid-19), declining revenues, and large amounts of debt.

Nobody was touching it – in fact, hedge funds were heavily shorting it.

As a result, it ended in a ridiculously undervalued position, with Price to Book around 0.2 and EV/EBIT at 0.15.

All it needed was a “spark” to rip higher – in this case, a mix of contrarian investors: Michael Burry of “The Big Short” fame, and a bunch of amateur investors on Reddit who wanted to take it out on professional hedge fund managers.

The whole thing was really a saga blown out of proportion (you can watch an interesting documentary about GameStop on Netflix, you’re welcome for the recommendation).

What’s interesting, though, is that two years later – even as the “saga” has blown over, leading to losses for most of the amateurs who bought late or believed in the “we’re sticking it to the hedge fund” thing – the price is still much higher and fairly stable.

So why would anyone buy a deep trash stock?

Take a look at this study.

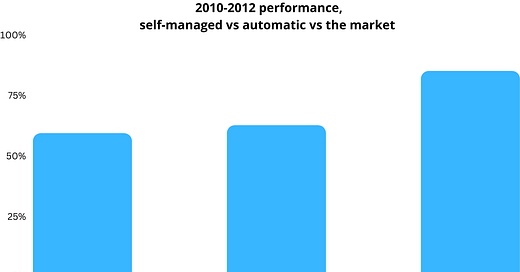

In 2013, Joel Greenblatt (investor, professor at Columbia University, and author of “The Little Book That Beats The Market”) looked at how investors performed when using something he called the Magic Formula. This formula more or less filtered companies based on how undervalued they were.

Greenblatt’s firm offered two choices for investors wishing to use the Magic Formula: a “self- managed” account and an “automated” account.

The self-managed one allowed clients to choose their own stocks from a list of approved Magic Formula ones. He also offered investors guidance on when to buy and sell, etc, but it was all up to them what to do when. The automated one simply bought and sold based on the formula alone. The study took place over two years.

This is what happened:

Even with the stock screener (the Magic Formula), the buy and sell “signals”, and world-class guidance, investors still failed.

Why?

Simple: self-managed investors “reliably and systematically” avoided the best performers.

Greenblatt has a great explanation for this: cheap stocks are cheap because they look like losers. We – investors – know that buying undervalued stocks is a good strategy. But we can’t help it. We’re too focused on the apparent risks. We focus on the near-term problems the company has and ignore what we’re supposed to do: buy low, sell high.

As a result, many of Greenblatt’s self-managed investors eliminated the worst looking stocks from the Magic Formula shortlist.

And it was these that turned out to be the biggest winners.

Think of it this way: a quality cheap stock might trade at 50% of book value (how many assets it has) and become a 2 bagger – meaning you make twice your money invested in it.

Meanwhile, the “complete trash” stock that no one would touch trades at 10% of book value and if it “mean reverts”, it may become a 10 bagger – meaning you make 10 times your money. Maybe even more if it can improve its value during the process, for example by negotiating its debt and improving its balance sheet.

The better the company, the better the metrics, the less mean reversion you should expect.

Whereas the trashier one only needs the smallest improvement (or even perceived improvement) to take off.

An amateur investor who became famous for doing this? Keith Gill via the Youtube channel Roaring Kitty – who later became famous for starting the GameStop saga we just looked at.

So how to invest in “deep trash”?

Think long and hard if this is for you.

Remember the Greenblatt study we talked about earlier?

He also found out that the self-managed investors tended to sell right after periods of bad performance, and then tended to buy after periods of good performance. They then held more cash and bought back only after period of performance.

In other words, they bought low, sold lower, waited, then bought back at a higher price. There are very few worse strategies out there.

It’s easy to get discouraged when investing in undervalued companies. Seeing the market (or worse, friends) do better than you can be emotionally draining.

That’s why knowing yourself as an investors and what you can “stomach” is the important and hard part.

Like Waren Buffet said:

“Investing is simple, but not easy.”

Diversify.

The difference in performance between investing in “quality undervalued companies” and investing in “companies nobody would touch” is that quality is already priced in.

The market is not stupid – but it is emotional.

It’s scared of taking certain risks and that's why some of these stocks are nearly given away. That’s why you need a portfolio diversified enough to account for the very real risks that make those trashy stocks scary for the market. You’ll need to factor in the risk that a substantial portion of "deep trash" stocks go to zero over time.

This is why these companies are also often called “value traps” or “falling knives”.

Look for the lowest of the low on traditional metrics

P/E ratio, P/B ratio, and EV/EBIT.

You can easily find them using a stock screener like Simply Wall Street.

Look beyond traditional metrics

A common one is high value of debt. You will rarely see a stock with earnings trade at 10% of book value unless the future cash flows are not enough to pay the debt, and bankruptcy is a real short term risk. Eventually the creditors will ask for their money back – in which case a fire sale of the assets combined with a low p/b would be sufficient to both pay the creditors and have a juicy “terminal value” for investors. And if the company does fix its debt problem, then that also can cause its price to jump.

Other times, the traditional value investing indicators (P/E etc) might not work at all – for example if the company is not making a profit. In this case a metric like EV/EBIT (which is great for finding quality undervalued stocks) won’t help you, and you’ll need to dig in deeper to see if there is any value left in the company at all. Fraudulent companies also have no earnings…

Perhaps try smaller “deep trash” companies first

Since their trading volume is lower, you only need a small amount of “price discovery” to have the price jump by 10x or more. Harder to do that with a large company like Apple.

Investing in “deep trash” stocks is a risky strategy. And also an emotional one. But buying clearly overpriced companies when the hype is high and the chart goes vertical can be as risky.

Maybe something you need to share with a friend?