Same as Ever by Morgan Housel: summary & investing lessons

“Look backward, and be broad. Rather than attempting to figure out little ways the future might change, study the big things the past has never avoided.”

I just finished reading ‘Same as Ever’ by Morgan Housel – a book I was excited to pick up. His previous blockbuster, ‘The Psychology of Money’ really inspired me to both reconsider my investing approach and to start MarketScouts.

The main point of his new book is that while things change, human psychology stays the same.

For investors, this means that instead of trying to forecast which way the markets will go or which companies or products will win, we should do the opposite:

“Look backward, and be broad. Rather than attempting to figure out little ways the future might change, study the big things the past has never avoided.”

So I thought it would be a good idea to share my highlights with you, while focusing on the most important lessons that the book has for us investors.

Lesson 1: forecasting is impossible

Every current event has a family tree of other events that you simply can’t understand. It’s too much information. As Housel says:

“Here’s an example: What caused the 2008 financial crisis? Well, you have to understand the mortgage market.

What shaped the mortgage market? Well, you have to understand the thirty-year decline in interest rates that preceded it.

What caused falling interest rates? Well, you have to understand the inflation of the 1970s.

What caused that inflation? Well, you have to understand the monetary system of the 1970s and the hangover effects from the Vietnam War.

What caused the Vietnam War? Well, you have to understand the West’s fear of communism after World War II . . . and so on forever.”

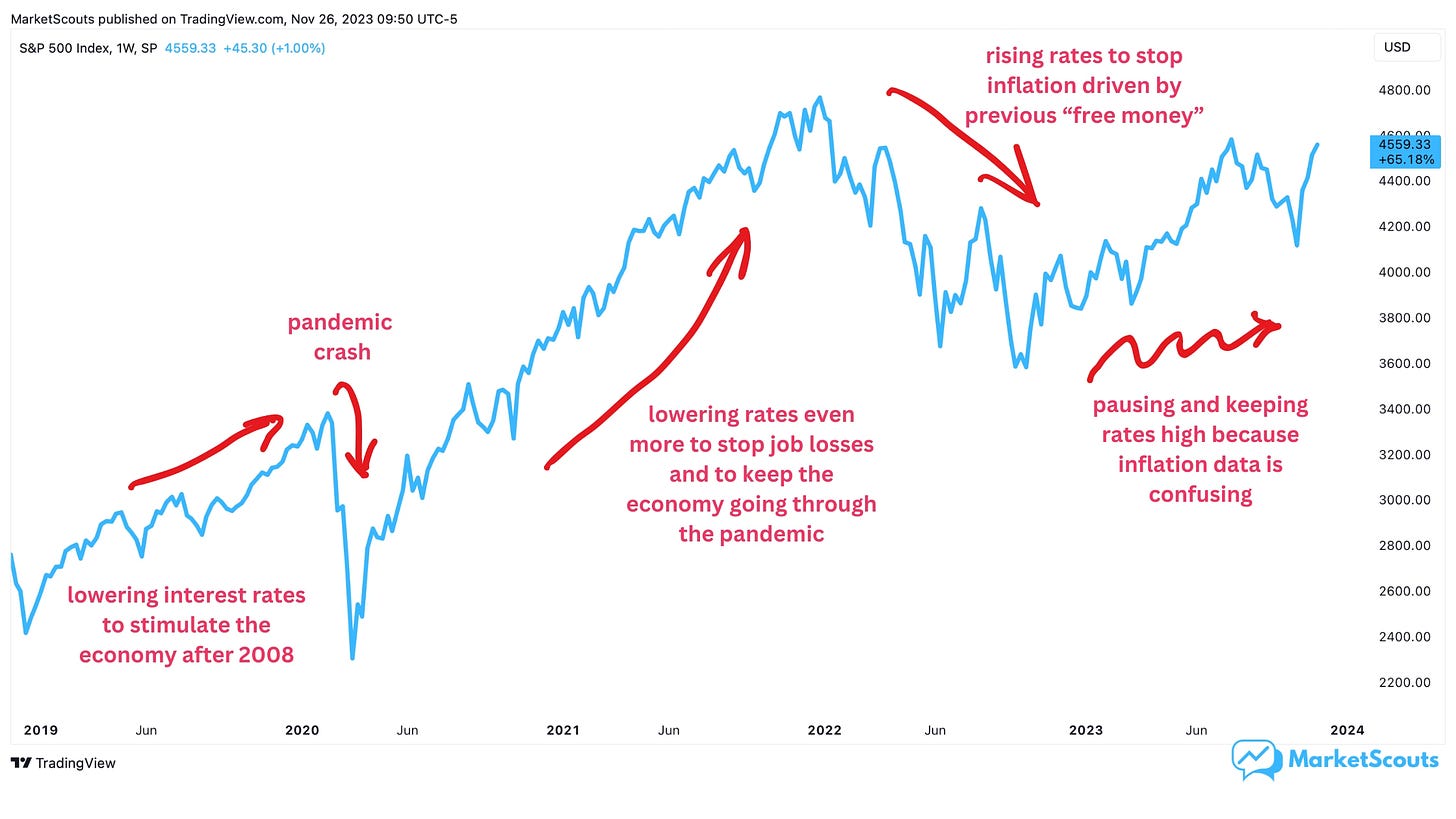

Just think of the past five years, when one thing led to another in a way that both seems obvious in retrospect and was shocking at the time:

Lesson 2: but behaviors stay the same

This is in many ways the main takeaway from the book.

“Predicting what the world will look like fifty years from now is impossible. But predicting that people will still respond to greed, fear, opportunity, exploitation, risk, uncertainty, tribal affiliations, and social persuasion in the same way is a bet I’d take.”

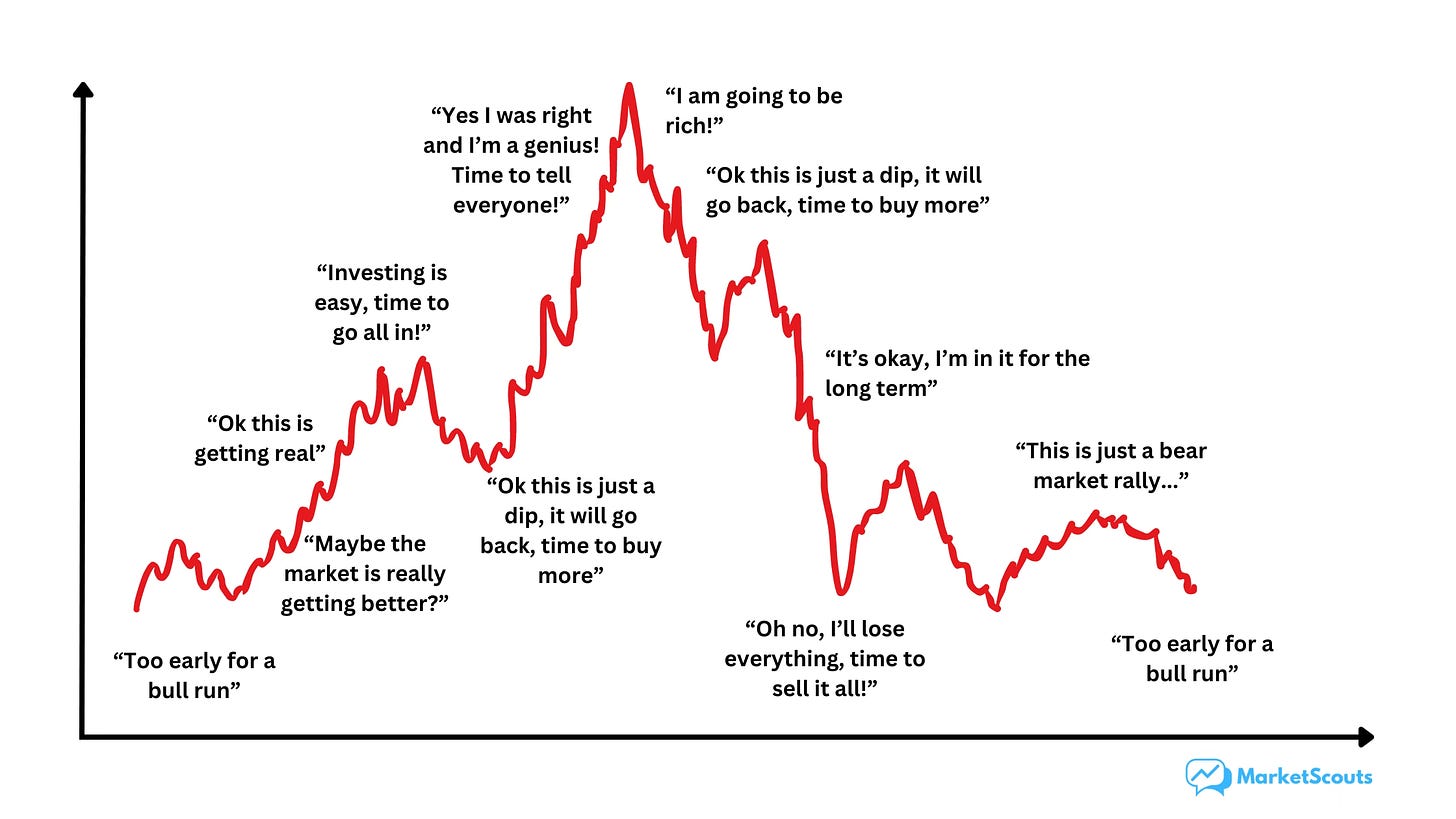

For example, think of the typical stock market, real estate, or crypto bubble. The asset might change, but what investors tell themselves never does.

Lesson 3: don’t wait for a forecast to prepare for risk

Housel has a great point here: The Economist publishes a forecast of the year ahead each January. But check out its January 2020 issue: not a single word about COVID-19. Its January 2022 issue does not mention a single word about Russia invading Ukraine either. But both of these events happened, seemingly out of nowhere, and took the economy and markets down with them.

But Housel has a great piece of advice:

“In personal finance, the right amount of savings is when it feels like it’s a little too much. It should feel excessive; it should make you wince a little.

The same goes for how much debt you think you should handle—whatever you think it is, the reality is probably a little less.

Your preparation shouldn’t make sense in a world where the biggest historical events all would have sounded absurd before they happened.”

In other words, being pessimistic in the short run can help you afford to be an optimist in the long run.

Lesson 4: valuation is simply a number from today multiplied by a story about tomorrow

“Investor Jim Grant once said: To suppose that the value of a common stock is determined purely by a corporation’s earnings discounted by the relevant interest rates and adjusted for the marginal tax rate is to forget that people have burned witches, gone to war on a whim, risen to the defense of Joseph Stalin and believed Orson Welles when he told them over the radio that the Martians had landed.”

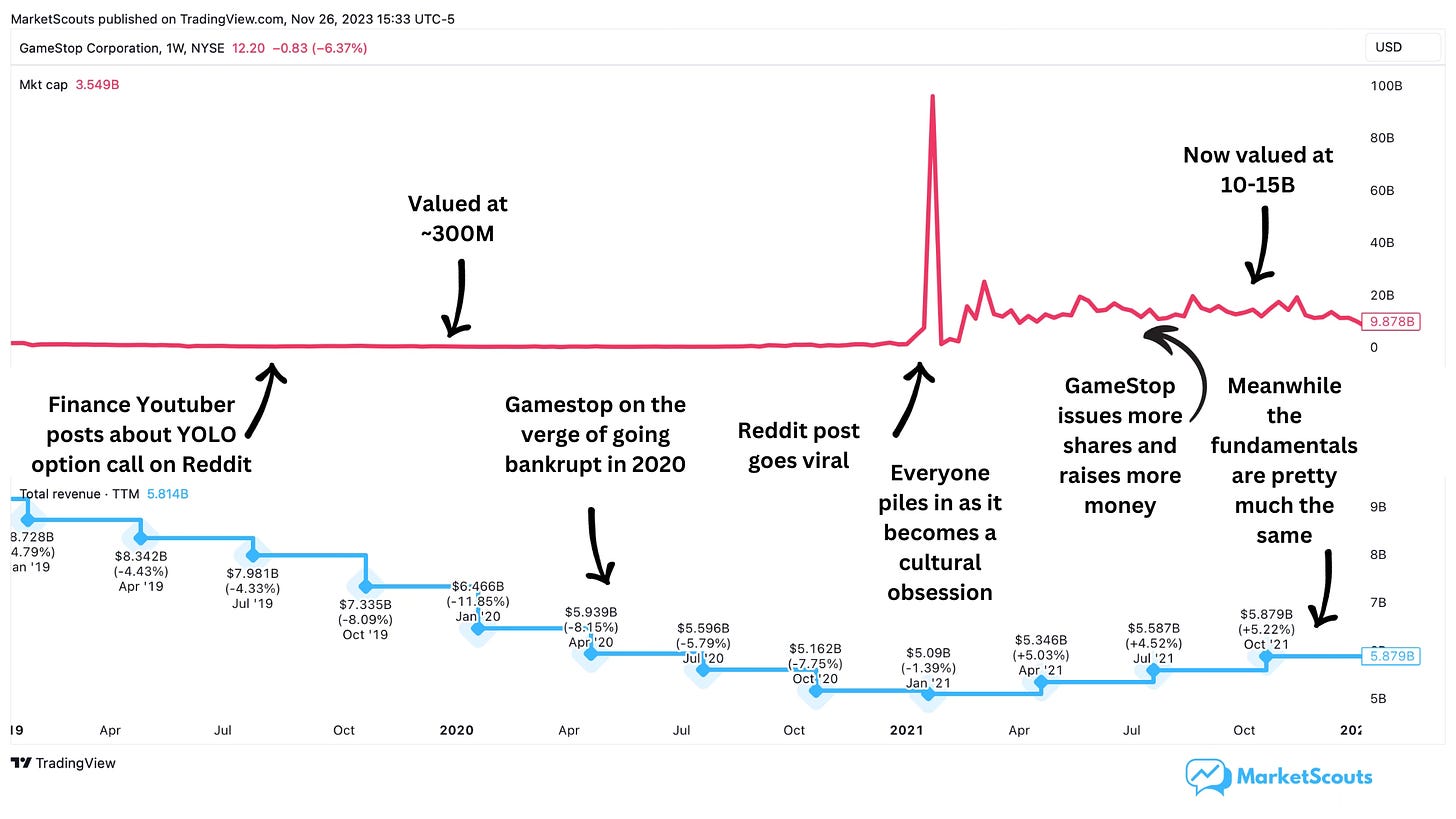

The best example of this is what happened to GameStop: it went from about $300 million in market cap to almost $100 billion for a day and then settled at about $15 billion. All without any significant changes in the underlying business.

Housel also quotes economist Per Bylund:

“The concept of economic value is easy: whatever someone wants has value, regardless of the reason (if any).”

Perhaps this explains how we live in a world where banks can both say things like “most crypto lacks use cases and it’s junk” while applying for crypto ETFs. The use case is less relevant than the fact that someone is willing to buy them.

Lesson 5: crazy is normal

Most “serious” investors are completely shocked every time a bubble happens. And especially after it has bursted.

“Every few years there seems to be a declaration that markets don’t work anymore—that they’re all speculation or detached from fundamentals.

But it’s always been that way. People haven’t lost their minds; they’re just searching for the boundaries of what other investors are willing to believe.”

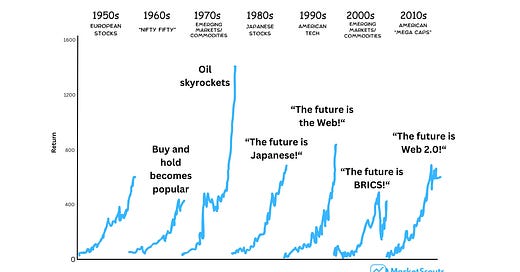

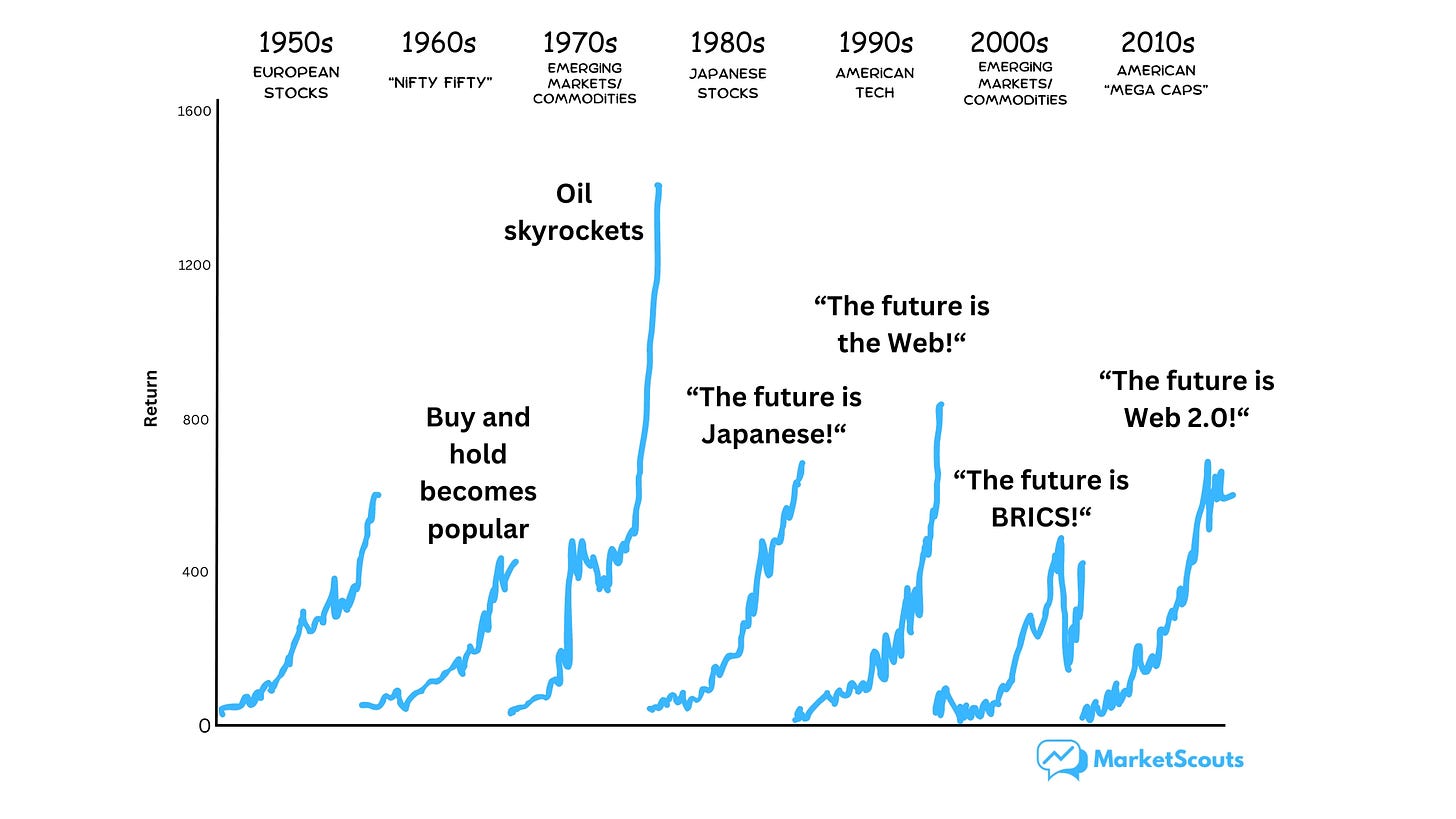

Just look at how every decade we got a new investment theme that got everyone excited and soon turned into a bubble:

Lesson 6: compounding is your best friend

In investing, you can miss being in the top 25% of investors each year but still be in the top 1% after twenty years or more.

That’s because of two things: one, aiming to be in the top performers each year means that you’ll take a ton more risk; two, the real magic happens in compounding.

“The most important question is not “How can I earn the highest returns?”

It’s “What are the best returns I can sustain for the longest period of time?”

Making 100% in a year feels great, and those are the stories that we all like to talk and read about. But a strategy that easily returns 100% one year usually crashes your portfolio -90% the next.

We wrote a while back about how more conservative portfolios can actually beat the market over the long run, as they don’t drop as much during market crashes.

Lesson 7: most competitive advantages eventually die

In other words, your favorite individual stocks might not make it as a very long-term investment.

Housel gives the example of evolution, where some species tend to get larger over time – only to be first in line for extinction events. He quotes a scientific paper that explains why:

“The tendency for evolution to create larger species is counterbalanced by the tendency of extinction to kill off larger species.”

This applies well to companies too. Never be surprised when something that dominates one era dies off in the next. Just look at how the main 10 companies in the S&P 500 index changed over time.

Lesson 8: everyone else has different incentives from you

This is one of my favorite points from the whole book. Everyone in the market has an incentive. And that incentive is not the same as yours.

Finance media has one incentive…

“Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal says there are three ways to be a professional writer:

1. Lie to people who want to be lied to, and you’ll get rich.

2. Tell the truth to those who want the truth, and you’ll make a living.

3. Tell the truth to those who want to be lied to, and you’ll go broke.”

People selling financial products have another incentive…

“Everyone knew the subprime mortgage game was a joke in the mid-2000s. Everyone knew it would end one day.

But the bar for a mortgage broker to say ‘this is unsustainable so I’m going to quit and deliver pizza again’ is unbelievably high.

A lot of bankers screwed up during the 2008 financial crisis.

But too many of us underestimate how we ourselves would have acted if someone dangled enormous rewards in our face.”

Even I have a different incentive – to get you to read and like MarketScouts articles.

And none of these are the same as your incentive, which might be a comfortable retirement, or to pay your kids’ college tuition, and so on.

So maybe read fewer 2024 market outlook pdfs from Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and others investment firms. And maybe unsubscribe from WSJ or Bloomberg while you’re at it, too. Or at least take what they say with a heavy pinch of salt.

Lesson 9: everything worthwhile has a price

We all know that long-term investing and compounding is the right strategy. That avoiding the panic but also the memes is the right approach. But that’s easier said than done.

“Saying ‘I’m in it for the long run’ is a bit like standing at the base of Mount Everest, pointing to the top, and saying, ‘That’s where I’m heading.’ Well, that’s nice.”

If we want to succeed as long term investors, Housel suggests we ask ourselves three questions.

First, how can we endure a never-ending parade of recessions, bear markets, meltdowns, meetups, surprises, and memes? Can you stick to your strategy when you see headlines like these?

Second, are our spouses, families, and friends there for the ride?

“An investment manager who loses 40 percent can tell his investors, “It’s okay, we’re in this for the long run” and believe it.

But the investors may not believe it. They might bail. The firm might not survive. Then even if the manager turns out to be right, it doesn’t matter—no one’s around to benefit.

The same thing happens when you have the guts to stick it out but your spouse doesn’t.”

Third, can we admit to ourselves if we made a mistake and change our minds?

“Long-term thinking can become a crutch for those who are wrong but don’t want to change their mind. They say, ‘I’m just early’ or ‘Everyone else is crazy’ when they can’t let go of something that used to be true but the world has moved on from.”

Lesson 10: what you haven’t experienced might change what you believe

You can read and study and come up with a strategy. But you often have no clue what you can stomach until it’s happened to you.

If I, today, imagine how I’d respond to stocks falling 30 percent, I picture a world where everything is like it is today except stock valuations, which are 30 percent cheaper.

But that’s not how the world works. Downturns don’t happen in isolation.

The reason stocks might fall 30 percent is because big groups of people, companies, and politicians screwed something up, and their screwups might sap my confidence in our ability to recover.”

This is important to keep in mind for two reasons.

First, it’s good to be a bit humble about your investment strategy. Don’t assume you’ll buy the dip when others sell. Which is why it’s so important to automate your investing. Dollar cost average – anything, just dollar cost average.

Second, be kinder to yourself. Finance influencers who mock people who panic sell probably have never experienced a real crash in their lifetime. And the same for you – when your conservative friends tell you about how they just keep everything in a savings account don’t show off your crypto gains. As Housel says, ask yourself:

“What have you experienced that I haven’t that makes you believe what you do? And would I think about the world like you do if I experienced what you have?”

Some final thoughts

Overall, ‘Same as Ever’ is a great book. Light and short, yet at the same time filled with examples and ideas that got me thinking.

The lessons I shared here aren’t even all of them.

A few others that are important but I’d run out of space if I wanted to talk about them in detail are:

Lower your expectations. Montesquieu wrote 275 years ago, “if you only wished to be happy, this could be easily accomplished; but we wish to be happier than other people.”

Accept that the world is uncertain, and don’t trust in forecasts, price targets, or “signals” that claim to be accurate.

Everything feels unprecedented when you haven’t engaged with history.

Save like a pessimist and invest like an optimist.

Embrace lack of accuracy in forecasts, ratios, indicators, financial data. Good enough is good enough.

Don’t be impatient. Stocks pay a fortune in the long run but crush you when you demand to be paid sooner.

Be optimistic about progress. You never know what today’s innovations will lead to.

The grass is always greener on the side that’s fertilized with bullshit. The second half of Montesquieu’s quote is “Being happier than other people is always difficult, for we believe others to be happier than they are.”

Focus on permanent, not expiring information. When you read something, ask yourself: “Will I care about this a year from now? Ten years from now? Eighty years from now?”

There are no points awarded for difficulty. Complexity sells better. It gives us the illusion of control. Think of a complicated investing strategy versus a simple one. You know the simple one is better, but the complex one feels better. Plus, when we hear someone say something we don’t understand, it creates an aura of mystique around them, We might think they have an ability to think about a topic in ways we can’t. But that’s just an illusion.

And many more. All mixed with examples and little stories.

That’s not to say the book is perfect. Housel meanders quite a bit, and reminded me too often of how some people claim that most non-fiction books should just be blog posts.

Yes, ‘Same as Ever’ could be a very long blog post.

But what a blog post.

Have you read the book? Planning to? Just leave a comment below – I’d love to learn more about what you think about Morgan Housel and his books.

I’d also love to hear about your recommendations. Any investing books that you feel not many people know about?

Thanks for bringing this to my (and other readers´) attention! Very refreshing to take a step back and find a new perspective. Especially liked the part on incentives ... very true, and the Jason Zweig quote is frightening!

we need to seek after durable competitive advantages! as those will last a long time.