"Price of Time" book summary part 2: why central banks lowered rates for the past two decades.

Let's look at why central bankers experimented with low, zero, and even negative interest rates. This post continues our review and summary of “The Price of Time” by Edward Chancellor.

This post continues our review and summary of “The Price of Time” by Edward Chancellor – one of the most interesting finance books in a long time.

Its main premise is simple: central bankers have engaged in a experiment to push interest rates lower and lower – even under zero.

Why? Five reasons:

To target a very specific level of inflation (not above but not below, either). Most central banks somehow settled on 2%.

To avoid deflation

To avoid recessions

To avoid drops in the wealth of a nation – basically, crashes in the stock and property markets

And to increase productivity.

Let’s take them one by one.

Actually, the first two reasons are interconnected so let’s look at them together.

Keeping inflation and deflation in check

To simplify things, lowering interest rates means increasing the amount of money in the economy because banks lend more.

Rising interest rates have the opposite effects.

Central banks use interest rates as a way to tweak the economy, and to achieve a “low but digestible” level of inflation. So far most central banks have settled on 2% as a magic number.

However, the book makes the point that research doesn’t support targeting a specific level of inflation. In other words, there’s nothing magical about 2% inflation.

Yet somehow, central bankers became obsessed with this level.

“2 per cent acquired talismanic significance – what Governor Kuroda called a ‘global standard’. The number was written into the ECB’s constitution. It was constantly invoked by central bankers, as if repetition would help them to attain their aim.”

Just look at these quotes from various central bankers.

Janet Yellen, while Chair of the Federal Reserve:

“So let me be clear – 2 percent is our objective. We want to see inflation go back to 2 percent; 2 percent is not a ceiling on inflation. So we’re not trying to push the inflation rate above 2. It’s always our objective to get back to 2, but 2 percent is not a ceiling.”

Mario Draghi, while President of the European Central Bank:

“The ultimate and the only mandate that we have to comply with is to bring inflation back to a level that is close to but below 2 per cent.”

and

“There are no limits to our actions, within our mandate.”

Haruhiko Kuroda, while Governor of the Bank of Japan:

“There is no limit to monetary easing […] “The Bank of Japan would do whatever is necessary to achieve its target” […] It is no exaggeration that [ours] is the most powerful monetary policy framework in the history of modern central banking”

Good God.

The main challenge here is that there are no studies showing that a fixed inflation level is good. And not studies about the 2% level, in particular.

In fact, according to “The Price of Time”, economists disagree with the concept of a fixed inflation target.

“One problem with the inflation target, according to UCLA economist Axel Leijonhufvud, is that ‘a constant inflation rate gives you absolutely no information about whether your monetary policy is right.’ On the contrary, Leijonhufvud maintained, the target encourages central banks to pursue policies that undermine financial stability”

Even former central bankers openly regret it.

“As a former Governor of the Bank of England, Lord King’s prime responsibility had been to implement the 2 per cent inflation target.

After retirement in 2013, he openly questioned the limitations of this rule: ‘we have not targeted those things which we ought to have targeted and we have targeted those things which we ought not to have targeted, and there is no health in the economy.”

Or

“Another retired central banker, Paul Volcker, was even more critical of the inflation target. ‘I puzzle at the rationale,’ wrote the former Fed chief. ‘A 2 percent target, or limit, was not in my textbooks years ago. I know of no theoretical justification. It’s difficult to be a target and a limit at the same time.”

And both periods of high inflation and deflation, while painful in the short term, are natural, don’t last long, and put the economy in a better shape afterwards.

This is particularly true for deflation – especially the kind brought about by recessions.

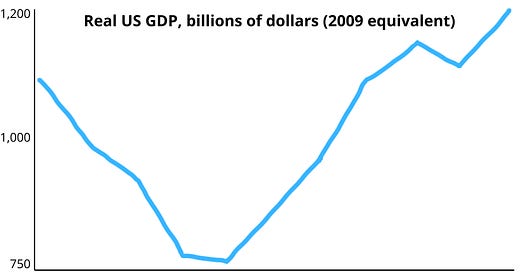

For example, the book gives the example of both the 1929 Great Depression and the 2009 crisis in Iceland.

These were followed by short and deep deflationary episodes – and then the economy came back roaring and healthier (less debt, higher profits, better jobs, higher wages, etc) than before.

Take the Great Depression. Despite the usual image that comes to mind…

“The Great Depression propelled productivity improvements across many other industries, ranging from airlines to warehousing. In his book The Great Leap Forward, Alexander Field of Santa Clara University claims that the 1930s were the most technologically progressive decade in American history.”

“As a result of productivity improvements across myriad industries America’s economic output eventually returned to its pre-Depression trend. Between 1929 and 1941, the US economy expanded at an annual rate of 2.8 per cent, in line with its long-term average. Americans growing up after the war suffered no permanent welfare loss. For the Greatest Generation, the Depression was just a traumatic memory.”

A traumatic memory that lasted only a few years, and from which the economy came back roaring.

Deflation is also more of a theoretical monster – in practice, deflation is inevitable if we look at productivity improvements.

That’s true especially for technology – and things impacted by technology, like clothes, food, energy, transportation, and so on.

Things get better and cheaper as we progress.

According to “The Price of Time”, both inflation and deflation are very complex and dynamic things, and changing the cost of capital to target a very specific (and largely unscientific) level can backfire – in ways central banks can’t imagine.

For example, inflation isn’t directly caused by low interest rates – but the credit cycle obviously is. So when interest rates are set too low, businesses with low efficiency find they can borrow money easily. This leads to the zombification of the economy (see part 1 of our review). New startups find it much harder to fight incumbents.

For example, we all see the word “startup” everywhere, but did you know that in the US, after the 2008 crisis, the rate of new business creation plummeted?

“The fever for start-ups didn’t spread far beyond Silicon Valley. In fact, new business formation in the United States fell sharply after 2008. In 2016, “business deaths outnumbered births for the first time since the Census Bureau started keeping records in 1978.”

Keeping recessions and crises at bay

Moving on from inflation and deflation, let’s look at point 3 and 4.

Chancellor makes a great point here: central banks have a mandate to stop crises from happening, so they have become addicted to pumping liquidity into stock markets and real estate markets whenever there’s a drop.

However, this constant bailing out of Wall Street has created a powerful addiction – investors and bankers have figured out that the Fed will always cut rates in the face of any hint of crisis.

Also known as “the Fed put”.

Oh, and this is not only happening in the US – central banks from China to Japan to Australia to Europe to the UK all behave in the same way.

This policy also maintains an illusion of wealth – “stocks always go up” and “property always goes up”.

Sure, this can lead to higher consumption due to false asset appreciation. It’s easier to spend if you think your investments are up and to the right. Which they are, on the chart, but at what cost to the economy in the long term?

Using low interest rates to boost productivity

The last reason that Chancellor gives as to why central bankers have pushed interest rate lower is also the most counterintuitive.

It is no secret that productivity growth is slowing worldwide.

For example, in the United States, it fell from 2.8% per year between 1947 and 1973 to 1.2% after 2010.

Things are worse in Europe and Japan, with productivity growing at less than 1% per year for a generation.

There are many reasons blamed for the slowing productivity: from aging populations to slower pace of technological innovation.

But Chancellor makes the point that none of these reasons are supported by evidence or data, and he sees low interest rates as the actual culprit.

Basically, central banks also see low interest rates as a way to increase productivity. The idea is that low rates would somehow make it easier for firms with high R&D spend (think cutting edge startups) to access capital.

According to The Price of Time, though, the exact reverse is happening.

When interest rates are low, it’s the largest, most inefficient firms that find it easier to raise capital.

On top of that, private equity firms proliferate – they benefit from low rates, as they borrow to buy companies, which will then be stripped for parts and sold for cash rather than reorganized and turn into sources of technological innovation.

See you in Part 3, where we'll cover the most important bit – how can we, as investors, use the insights from "The Price of Time"?

Expect many investment ideas and themes inspired by the book.

And, of course, please bear in mind that these are not financial advice. Do your own research, and keep learning.