"Price of Time" book summary part 1: what is interest, and what happens when interest rates are too low?

"The Price of Time" is one of those books that it's too important to skim over – so we broke the summary into 3 parts.

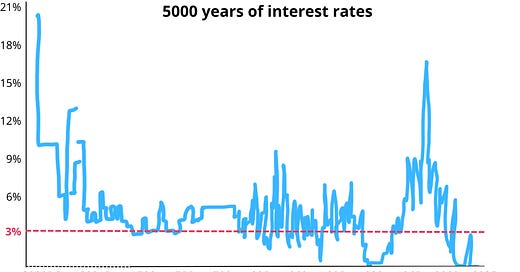

Did you know that after Lehman Brothers failed, central banks pushed interest rates to the lowest level in 5,000 years?

This is how Edward Chancellor’s The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest begins.

But this review won’t focus on the history bits. Chancellor seems to have read every book and essay about interest ever written, and the book literally starts with the very beginning of the story of interest, five millennia ago. There is a ton of history in this book, and we’ll let you enjoy it by yourself.

For now, we’ll look at what the book actually can teach an investor – specifically, a stock market investor.

As we do for all our book reviews.

The key investing takeaways from this book:

Real interest rates lower than either the rate of growth of the economy or 3% are incredibly damaging. Real interest rates are interest rates minus inflation – basically what you’re left with.

Central banks have started experimenting with this for the past few decades, for a number of reasons – and are now trapped in this experiment (low interest rates beget low interest rates as a “fix”).

This has increased inequality, supercharged whole industries (VC, gig economy, crypto, real estate), actually lowered real productivity and growth – and most importantly for investors, created an “everything bubble”

Every time something like this has happened in the past it has ended very badly: 90% crashes, decades of negative returns for investors, zombie companies, social unrest, and so on.

We’re approaching that moment (or at least it’s getting more difficult to keep kicking the can down the road).

Let’s dig in.

What is interest and what happens when you set it too low

Most people think of interest as something bad: “hey why are you charging money for basically doing nothing?”

"The Price of Time" reminds us that we’re not the only ones: thinkers and philosophers throughout history—from Aristotle and Aquinas to Proudhon and Marx—have regarded any rate of interest as unjust.

But the book makes the point that the practice of charging interest is natural and ancient – in fact, it predates money itself, with the first loans and interest being made in barley, wheat, or livestock. In fact, many of the old words for interest come from words related to harvest or offspring of livestock.

In fact, according to Chancellor, interest is not only natural, it is absolutely essential – an “universal price” at the base of an economy.

The book looks at the ways interest has been defined throughout history – each relevant to investors.

Setting interest too low or at zero ignores these definitions, creating specific imbalances:

Interest as the time value of money (“price of time”)

We want stuff now and not in the future.

That's because humans have a positive time preference.

“The Marshmallow Test shows that humans, or at least pre-schoolers, are impatient. They exhibit positive ‘time preference’. The bonus marshmallow can be seen as a kind of interest.”

People also value future income less because it should be bigger than what it is now.

At least if the economy is growing.

“It may also be the case that humans are congenitally short-sighted and underestimate their future wants. And, even if none of the above held true, when an economy is steadily expanding most people can expect to become richer over time; since their future income exceeds their current income, people will value it less.”

Interest also enables us to value money at different points in time.

No interest, no way to value anything: property, cash, stocks, dividends, you name it.

“Interest – the time value of money – lies at the heart of valuation. At the turn of the eighteenth century, the brilliant Scotsman John Law wrote that ‘anticipation is always at a discount. By discounting the future cash flow generated by a stock, bond, building or any other income-producing asset, interest allows us to arrive at its present value.”

Interest as an incentive for money to move

First, if you have a healthy level of interest, people lend out their money. No interest, no reason to give your money to someone else.

The lending of money is absolutely necessary if you want anything to happen in an economy.

Obviously if interest is too low, money doesn’t "know" where to go, and people take much more risk than they would otherwise.

“If interest rates are kept below their natural level, misguided investments occur: too much time is used in production, or, put another way, the investment returns don’t justify the initial outlay. ‘Malinvestment’, to use a term popularized by Austrian economists, comes in many shapes and sizes. It might involve some expensive white-elephant project, such as constructing a tunnel under the sea, or a pie-in-the-sky technology scheme with no serious prospect of ever turning a profit.”

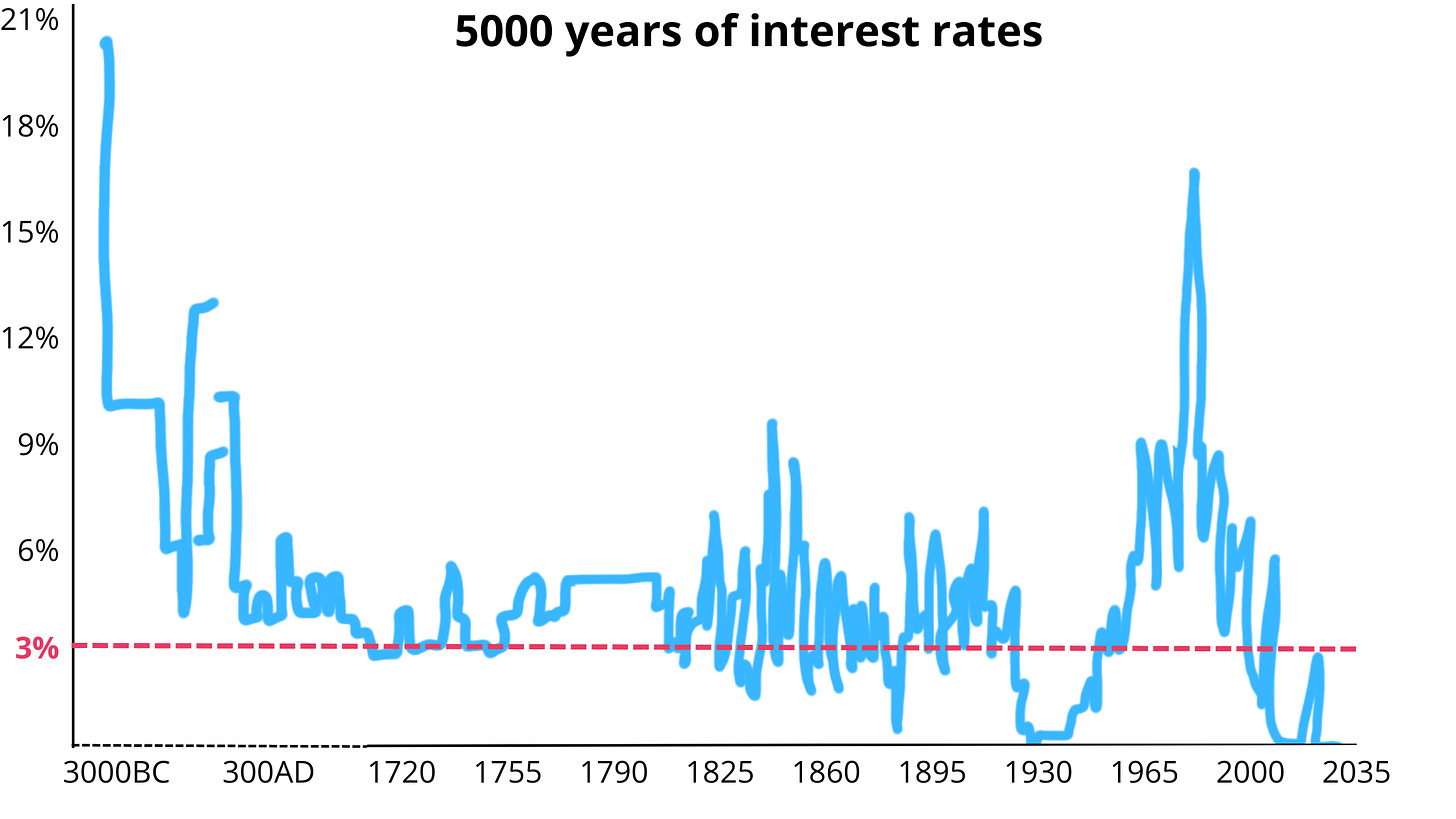

Interest as a reward for saving (“wage of abstinence”)

Interest as a “wage of abstinence” means simply: money you get as a reward for saving.

Look at what happens when interest goes under 3% - saving is no longer viable. You just have to take more risk if you want to be able to retire.

Interest as a cost of production (“hurdle rate”)

“Interest turns time into a cost of production. Time is money. Entrepreneurs who save time in production, who bring goods most quickly to market, emerge as winners in the game of creative destruction. Interest rations capital. From this perspective, interest is not a deadweight but a spur to efficiency – a hurdle that determines whether an investment is viable or not. ”

In other words, a healthy interest rates level helps the natural selection in the economy and keeps the economy healthy.

Low rates drive capital into projects with lower-than-normal expected returns; in other words, cheap money decreases the natural “hurdle rate” for investment.

The book argues that over the past two decades, this has had 3 consequences:

First, we got a ton of companies that had no idea how to turn a profit. Uber, WeWork, and the like – who basically used investor cash to subsidize “negative margin” services.

Negative margin sounds cute, but it basically meant that they burned $2 to earn $1.

Second, we got zombie companies kept alive by cheap debt.

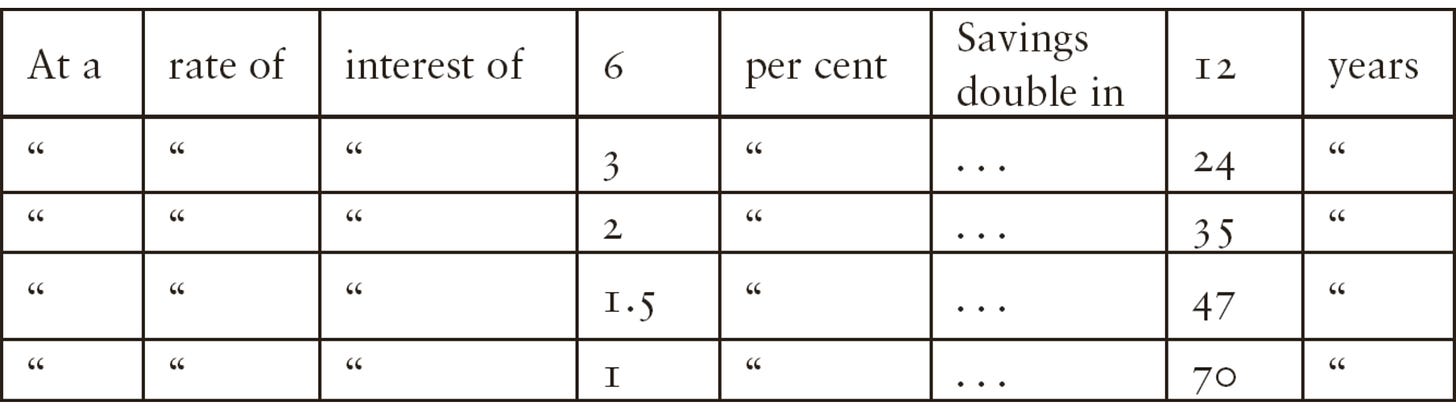

Look at what happened in Japan when interest rates were kept too low too long. The market first got a massive bull run, then a crash which took decades to recover from:

...while its economy has become zombified through the entire experience.

“After the collapse of Japan’s Bubble Economy, a graveyard full of corporate zombies arose in the East. In the first half of the 1990s Japanese banks decided to roll over (‘evergreen’) their non-performing loans rather than recognize losses. ‘Unnatural selection’ started to determine the allocation of capital. Later studies showed that loss-making Japanese firms enjoyed better access to bank credit than profitable ones.”

In any case this has been happening for the past decade in Europe as well.

“Zero interest rates kept loss-making companies on life support. By 2016, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that 10 per cent of firms were unable to cover their interest payments from profits – the OECD’s definition of a zombie. Europe, it seemed, was turning Japanese.”

The book makes a great point comparing interest rates with forest fires. Small forest fires might be scary but are incredibly important to the health of the forest.

When the US Forest Service started putting them out, we actually got fewer but much larger and devastating fires as a result.

“The more fires the Forest Service put out, the more extensive fires became. While small fires in the forest destroy with precision, great conflagrations wreak indiscriminate damage, killing even the healthiest trees.”

Fed worked in the same way: it suppressed economic volatility and encouraged the build up of hidden financial leverage, ignoring the long term consequences of their actions.

“Drawing a parallel between the US Forest Service and Federal Reserve is irresistible. The Fed was created less than a decade after its environmental counterpart. By the 1920s the Fed was attempting to suppress the business cycle. While ‘federal fire suppression acts to subsidize developments of private lands in fire-prone areas’, the Fed’s policy of suppressing economic volatility encouraged the build-up of financial leverage.

Third, and possibly the most dangerous, capital flowed to the least productive areas of the economy, like real estate. Companies loaded up on debt and started to use it to buy back shares instead of investing in productive assets or R&D. Not to mention industry concentration and monopolies.

Look at what "financialization" did to General Electric (GE):

“In the years after 2008, at a time when several of GE’s divisions were being hollowed out, $46 billion was expended on share buybacks. After Immelt left in 2017, it was revealed that GE had paid dividends in excess of free cash flow.”

“In 2018, GE’s credit rating was downgraded to a notch above junk. By the end of the year, its shares were down more than 90 per cent from their peak under Welch.”

Yes, that's 90 (ninety!) percent down.

Interest as a risk-pricing tool (“price of anxiety”)

The book also calls interest the price of anxiety: the anxiety of being parted with your money for a while.

What this means is that interest is essential in pricing risk.

When interest rates are set too low, you can’t price risk adequately anymore.

“Finance in the twenty-first century is underpinned by the role that interest plays in pricing risk. An enormous variety of risks are incorporated into the rate of interest: credit risk (which can be divided into default and recovery risk), legal risk, liquidity risk and inflation risk. ”

As a result, investors become blind.

“The Federal Reserve policy of zero per cent interest rates and monetary expansion,’ commented James Grant, ‘has, by design, forced investors further out on the risk–return spectrum than they would otherwise have been had short-term real interest rates been positive.’ Grant compared low interest rates to ‘beer goggles’ which blinded investors to financial risk.”

Take tech companies. Basically, when interest rates are low, capital feels almost free. Companies like unprofitable tech startups become used to simply burning money to grow, with no plan of becoming a real business (“we’ll just raise a new round”). Investors in these companies start to believe capital will stay "almost free" forever.

Or think of crypto. Every time an exchange collapses or a coin is revealed to be a scam, the same line comes up: “with interest rates so low, people had no incentive to keep their money in the bank. Who can blame them for gambling?”

Or, to paraphrase Warren Buffett:

“Interest rates basically are to the value of assets what gravity to matter”.

Once this gravitational force is removed (through zero or even negative interest rates), speculative assets – from stocks, to bonds, to real estate, to cryptos – take off.

When are interest rates “too low”?

The book makes a valid point that it’s become clear for the past 20+ years that the rates have been under the “natural rate of interest”.

Below this level we get inflation – initially in asset prices, which means that it seems that we're all getting rich for free. Later it seeps into the economy.

Above this level, we get deflation.

And while economists argue what this level actually is, luckily for us investors, Chancellor does give us some starting points.

According to him, interest rates are too low when:

A. Benchmark interest rate < rate of growth of the economy, or

B. Real interest rates (interest minus inflation) < 3%.

Why 3%?

The book points out that it's mostly our psychology at work.

“Walter Bagehot, the Victorian era’s most famous financial journalist, liked to say, ‘John Bull can stand many things but he can’t stand two per cent.

Thank you for reading so far.

We believe "The Price of Time" is one of those books that it's too important to skim over, so we broke the summary into 3 parts.

See you in Part 2, where we'll discuss why exactly central banks have pushed interest rates so low – despite the important of healthy interest rates.

In Part 3 we'll cover the most important bit – how can we, as investors, use the insights from "The Price of Time"?

We'll cover investment ideas and themes inspired by the book. Although, of course, bear in mind that these are not financial advice.

Interesting! Can’t wait for the next part to read 🙌🏻