This study shows how everyday investors can beat the pros – and the index

It's all about conviction – and disagreement.

You’ve probably heard that active investors can’t beat the index.

The data seems to confirm it. Just look at how badly the average mutual fund lagged behind the S&P500.

And if they can’t beat the index, how can you, right?

Well, a paper by Randolph B. Cohen, Christopher Polk, and Bernhard Silli examined the performance of active managers' "best ideas" and came up with some surprising results.

Ok, what’a “best idea”?

The authors define "Best ideas" as the stocks that managers hold with the highest conviction, as measured by the degree of deviation from benchmark weights.

Basically, if you’d expect an average fund manager to sort of “copy” the index (what they call “closed indexers”), then the more a stock would be abnormally weighted in their portfolio, the more “conviction” the manager probably has.

The authors also found that the majority of the abnormal returns came from the best ideas that are the least popular, suggesting that managers mostly generate alpha in best ideas that other managers do not seem to have.

“Less than 18% of best ideas are considered as such by two managers, and roughly 8% of best ideas overlap three managers at a time. A stock is the best idea of more than five funds less than 7% of the time.”

Does it work?

The study looked at 300 active managers and their portfolios between 1994 to 2003.

So quite a bit of data.

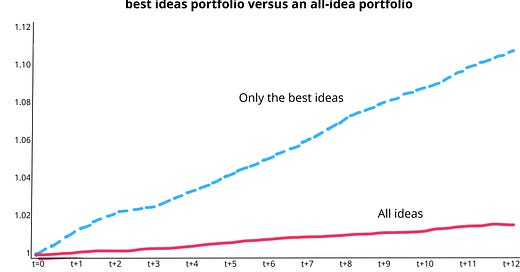

The authors found that these stock picks generated significant risk-adjusted returns over time and systematically outperform the rest of the positions in managers' portfolios.

If you’re interested in the actual numbers, we’re talking about an annualized alpha of 4.1% and a Sharpe ratio of 0.44, compared to an alpha of 0.7% and a Sharpe ratio of 0.08 for the rest of the positions in managers' portfolios.

Best of all, the authors also found that the abnormal performance appears permanent, showing no evidence of reversal over the subsequent quarters!

So, higher performance – with lower volatility – permanently.

Why don’t professional fund managers always invest like this?

The authors argue that the entire professional asset management industry is built in such a way that makes it easier for fund managers to sell “less-performing” portfolios to investors – instead of holding more concentrated portfolios.

What if each mutual fund manager had only to pick a few stocks, their best ideas? Could they outperform under those circumstances? We document strong evidence that they could, as the best ideas of active managers generate up to an order of magnitude more alpha than their portfolio as whole.

The typical mutual fund managers can, indeed, pick stocks. The poor overall performance of mutual fund managers in the past is not due to a lack of stock-picking ability, but rather to institutional factors that encourage them to over-diversify.

Those “institutional factors”?

legal requirements: literally, a number of regulations make it impossible for many investment funds to be very concentrated.

the desire to have a very large fund and collect more in fees. Classic.

but also the desire (by both managers and investors in the fund) to minimize a

fund’s volatility.

Basically, despite the scientific evidence, fund managers have to stick to a certain volatility. Their investors simply won’t stomach more.

This despite, of course, volatility being a poor measure of risk.

Like Warren Buffet said at the 2007 Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholder meeting:

Volatility is not a measure of risk. And the problem is that the people who have written and taught about volatility do not know how to measure risk. Past volatility does not determine the risk of investing.

Take it with farmland. Here in 1980, farms that sold for $2,000 an acre went to $600 an acre. I bought one of the them when the banking and farm crash took place. And the beta of farms shot way up. And according to standard economic theory or market theory, I was buying a much more risk asset at $600 an acre than the same farm was at $2,000 an acre.

That’s nonsense, that my purchase at $600 an acre of the same farm that sold for 2,000 an acre a few years ago was riskier.

But in stocks, because the prices jiggle around every minute, and because it lets the people who teach finance use the mathematics they've learned, they have, in effect, translated volatility into all kinds of measures of risk.

“Risk comes from not knowing what you’re doing. From not knowing what you’re investing in.”

But try explaining that to your churning insides as you’re watching your portfolio lose 30% in a month…

Moving on.

So, what’s the actionable conclusion here?

Strategy A: find top investors and copy only their “best ideas”.

To qualify as a best idea, it has to be:

unpopular: no other top investor seems to have it

and serious: it’s a significant percentage of the investor’s portfolio.

We’ll explore how to actually do this in an article coming soon – stay tuned!

Strategy B: when you’re doing your own homework and find your own stock picks, unless you’re truly excited about an idea, move on.

It’s ok to do nothing.

To quote Buffett again:

“The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot. And if people are yelling, ‘Swing, you bum!,’ ignore them.”

So, if you feel an idea doesn’t feel right, take a step back. Make a pros and cons list. Try to see the other side of the bet.

Perhaps use

‘s excellent Red Flag Checklist.In any case, keep in mind that this study isn’t quite “scientific”. It looked at a specific segment of the professional money management industry, in a specific country (the US), so who knows? Its findings might not apply everywhere and always.

Still, it’s a pretty compelling… idea.

If you found this piece of research interesting, please share it with your friends.