Do you really need to take more risk if you want higher returns?

There's one thing that your day trader friend and a financial advisor agree on: higher returns imply higher risks. But do they?

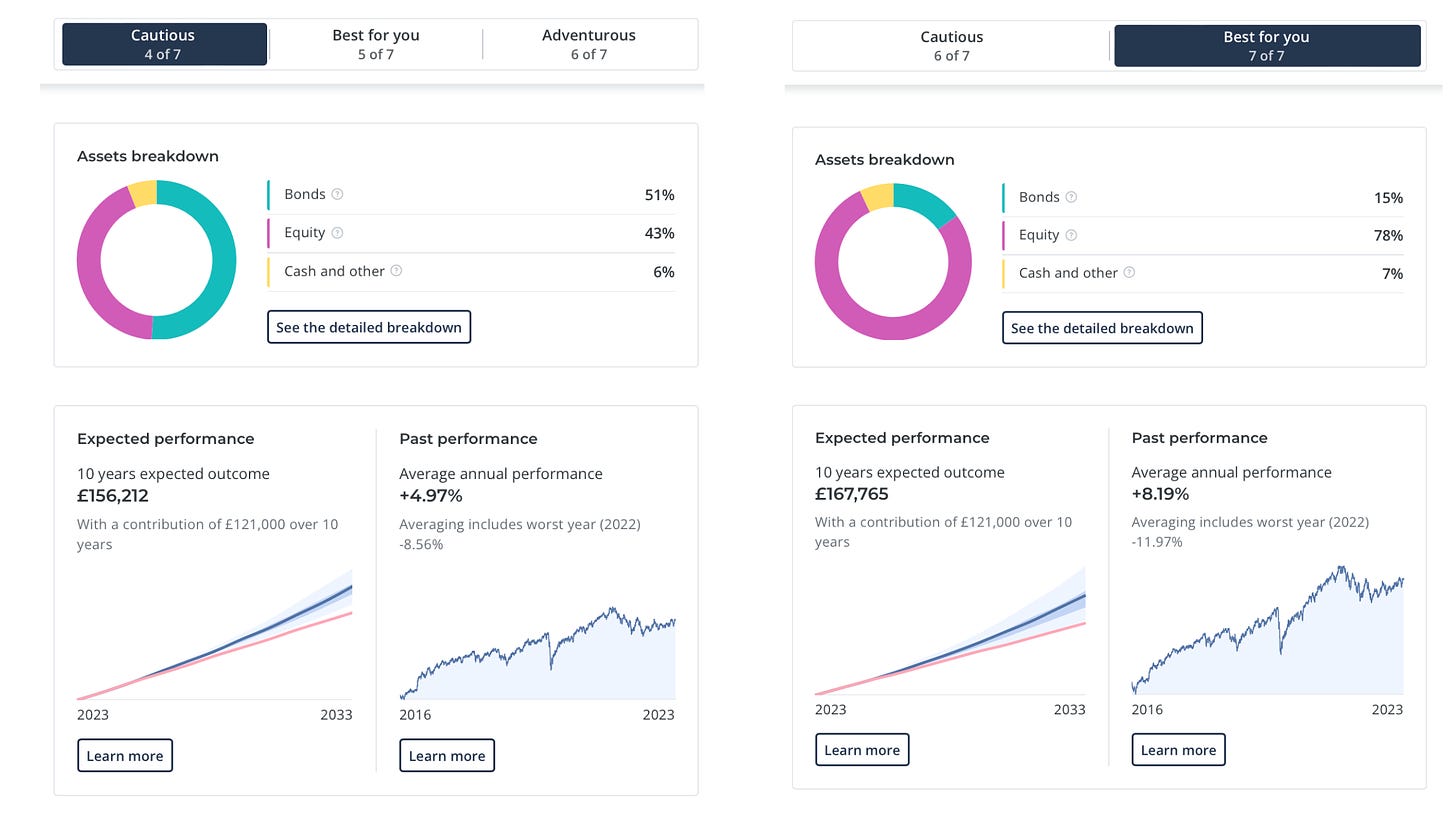

This is a screenshot showing a few options offered by Moneyfarm, one of the main robo-advisors in the UK:

Notice something?

It pretty much says “click on more risk = get more return”, basically.

Is it as simple as that?

How risk is usually defined

As an investor, you’re exposed to all sorts of risk: political risk, business risk, counter-party risk (for example, when bitcoin goes up but the exchange gets hacked), and so on. Life’s tough.

But that’s not what we’ll talk about here.

As an everyday investor, you’ll most likely see the word “risk” in the description of a portfolio choice in an robo-investing app or in the description of a fund.

What they refer to there is: the chance that the actual gain from an investment will be different from the expected one.

In other words: volatility 📈📉📈📉

So an investment that whipsaws up and down is labeled “riskier” than one that grows steadily.

And also “riskier” than one that slowly loses money!

A real-life example of risk and return

Let’s look at three ETFs that are often used in building the kind portfolios you find in automated investment tools: one “high risk”, one “medium risk”, one “low risk.”

Then we’ll see how they do in real life.

A “high-risk” ETF: VWO

The full name is Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index Fund ETF.

Vanguard labels it a 5 out of 5 on its risk scale, and says:

“Share value may swing up and down more than that of stock funds that invest in developed countries, including the United States”

That seems to make sense: emerging markets are growing but investors need to watch out for risks like political instability, currency volatility, and economic challenges. And that’s on top of the regular investing risks.

A “medium risk” ETF: VIG

VIG is the ticker for Vanguard Dividend Appreciation Index Fund ETF. It tracks companies “acknowledged for their consistency in increasing dividends for a minimum of ten consecutive years”.

Vanguard rates it a 4/5 in terms of risk.

Again, this seems to make sense:

companies paying dividends consistently are profitable, tend to be more mature, and generally more stable

they are also US-only companies. On one side, that tends to reduce volatility (it’s a developed economy) but can also increase it during crashes (“all eggs in one basket” sort of situation)

dividend-paying stocks are sensitive to changes in interest rates. When interest rates rise, dividend stocks may become less attractive compared to US Treasury bonds, for example.

A “low-risk” ETF: VTEB

Also known as the Vanguard Tax-Exempt Bond ETF, it tracks an index of tax-exempt municipal bonds from US states and local municipalities.

Vanguard gives it a 2/5 on its risk scale.

What makes it low risk?

bonds are generally rated as less risky than stocks

municipal bonds are less risky than corporate bonds: local governments are less likely to default (“not pay”) compared to companies. Especially US municipal bonds

they’re tax-exempt, which can increase the after-tax earnings investors get.

How do they compare?

If you traveled in time to 2018 and opened an account with a robo-advisor, you’d probably see something like this:

(We made up “Made Up Finance App”, please don’t try to sign up to it).

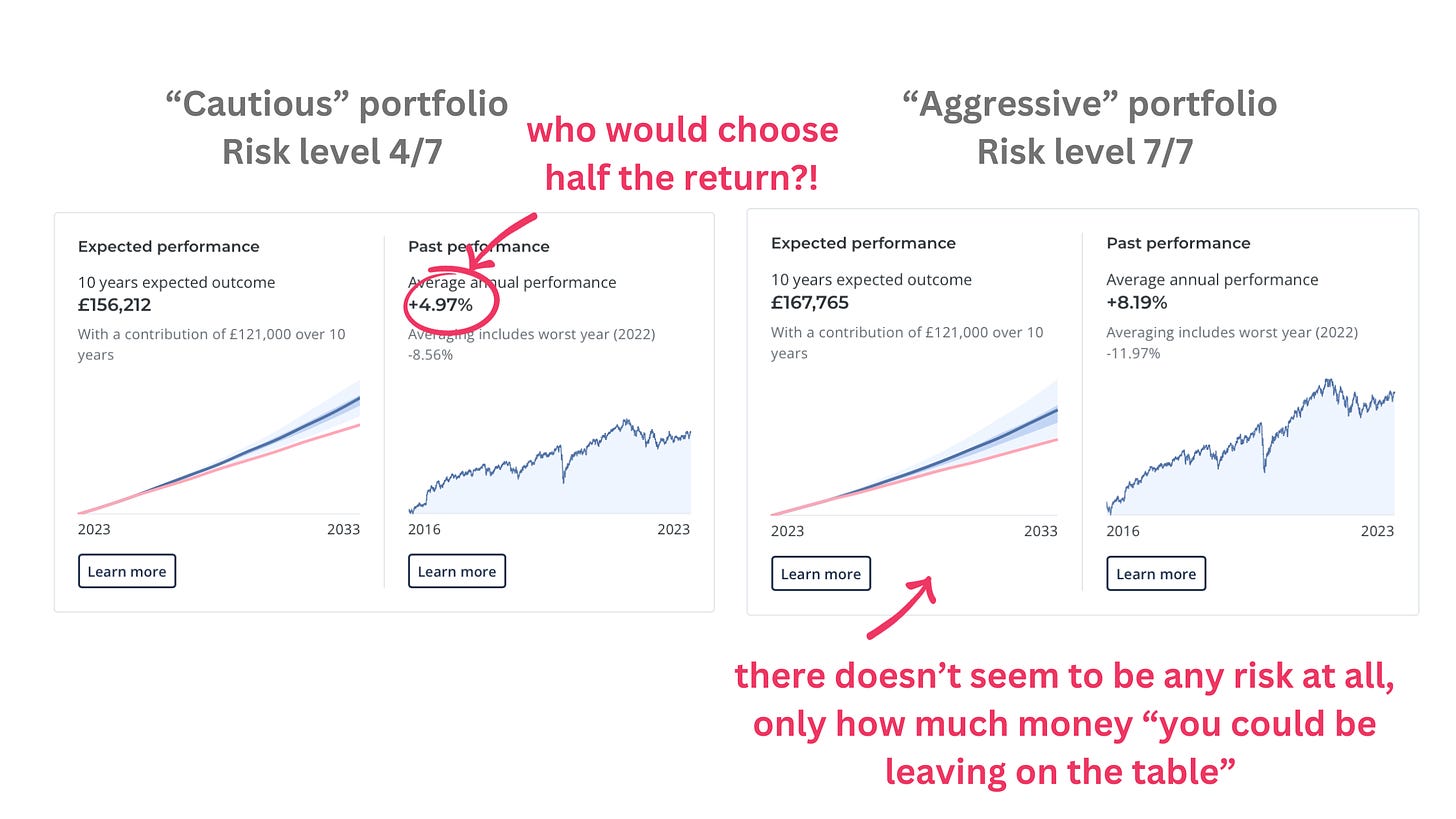

So essentially our fictional app says something like this:

the more risk you’re willing to take, the more return you should expect

the more risk you’re taking, the more volatility (ups and downs) you’ll see

but over a few years you should still see volatility “smoothened out”.

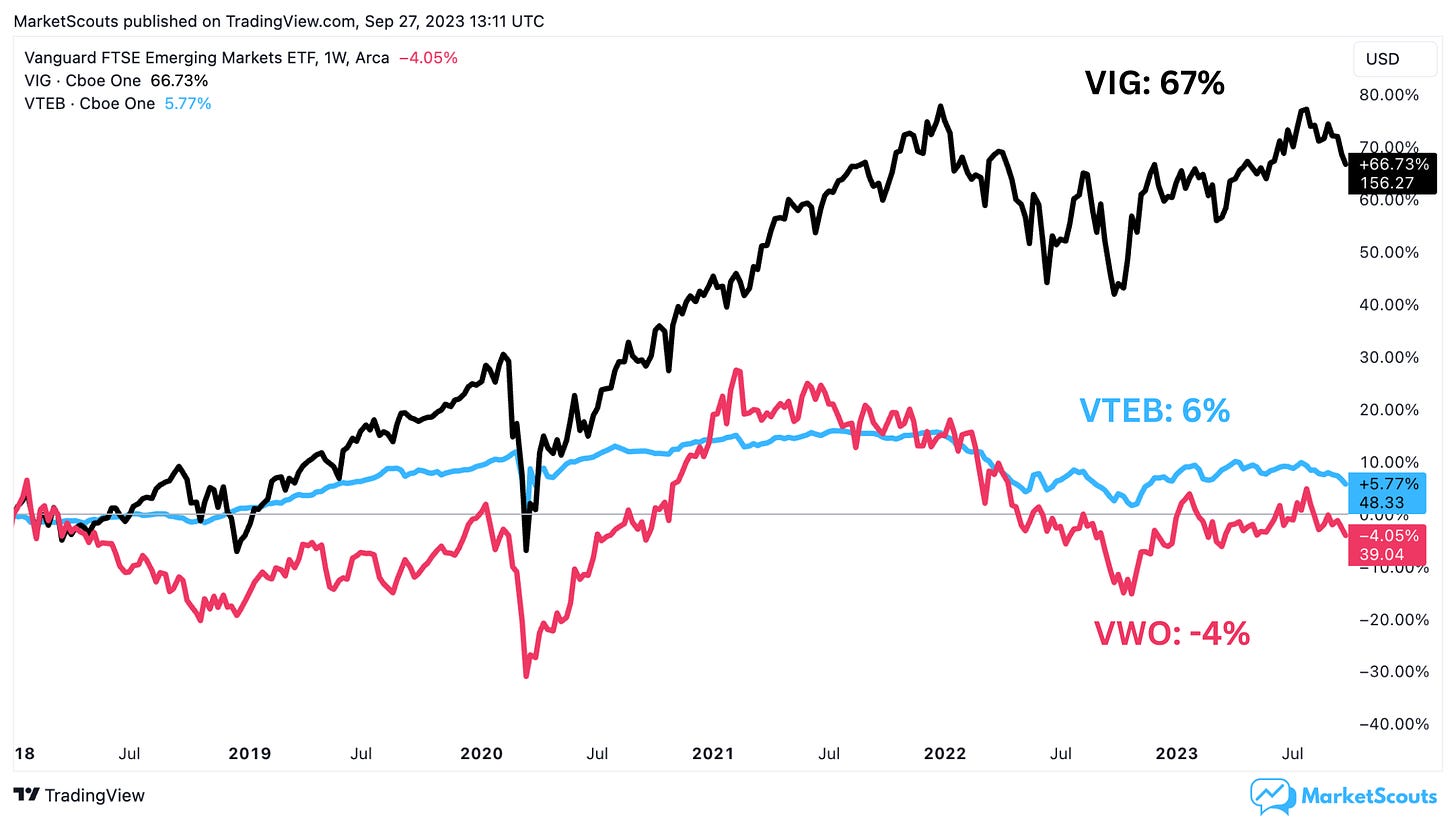

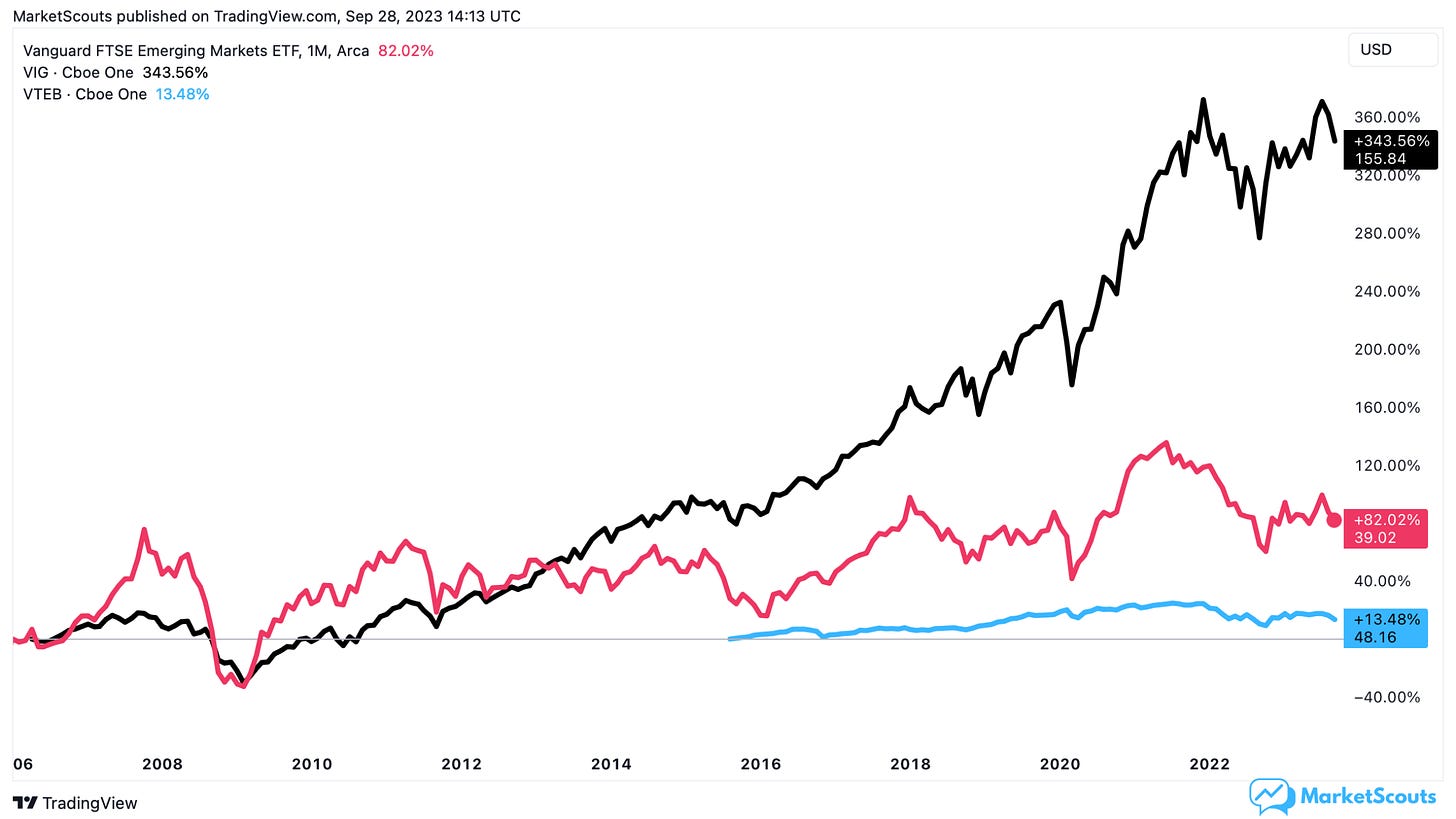

So let’s see how they actually performed since 2018:

What actually happened:

the high risk option had the lowest performance, but also less volatility than the medium-risk option: the highest peak was 82% and the biggest drop was 38%

the medium risk option had by far the best performance, and similar volatility with the high risk one: the most it gained was 92% and the biggest drawdown was 29%

the low risk option performed more or less as advertised, although volatility seems to have been a bit higher than you’d expect for a low risk fund made of bonds: it went from +22% to -15%.

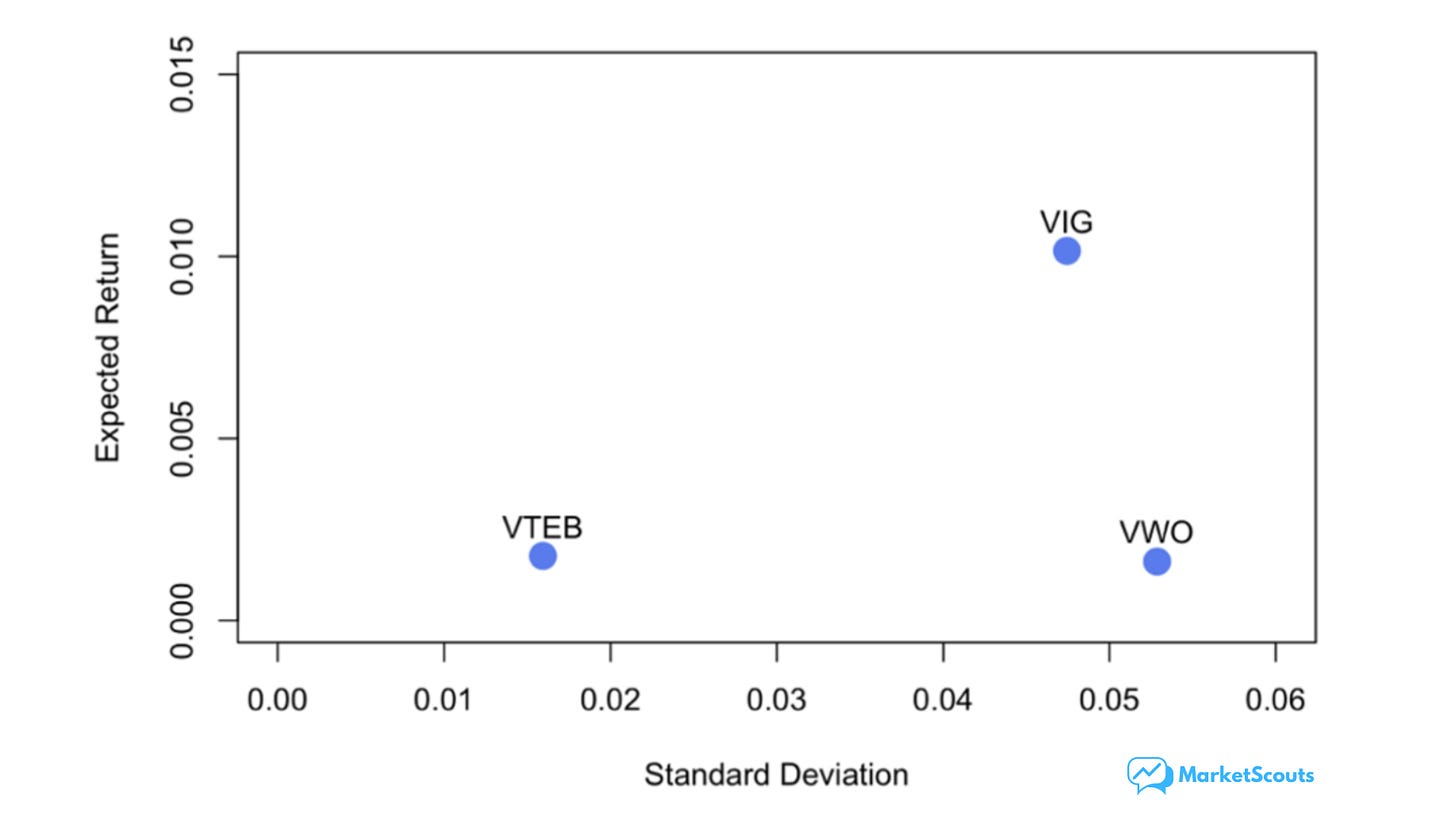

We actually ran the data and looked at the correlation between the risk and expected return using a software written in a programming language called R.

This is what we got:

To translate this graph into English:

VIG is not the riskiest asset but has the highest return

VTEB has minimum risk, minimal return

and the most fascinating bit: while VWO carries the highest risk, its expected return is almost as low as VTEB's – an ETF made of bonds! – which is definitely what you wouldn’t expect.

Why?

One explanation for the weak VWO performance could be COVID-19. The outbreak started in China, a big piece of the Emerging Markets Index (tracked by VWO).

As the pandemic spread, emerging economies were particularly affected.

Which takes us to the next point: if covid didn't occur, would VWO have the highest return?

We can’t know what “would have” happened, of course, but we can look at how VWO performed versus the other two over the long term:

So still pretty much the same thing!

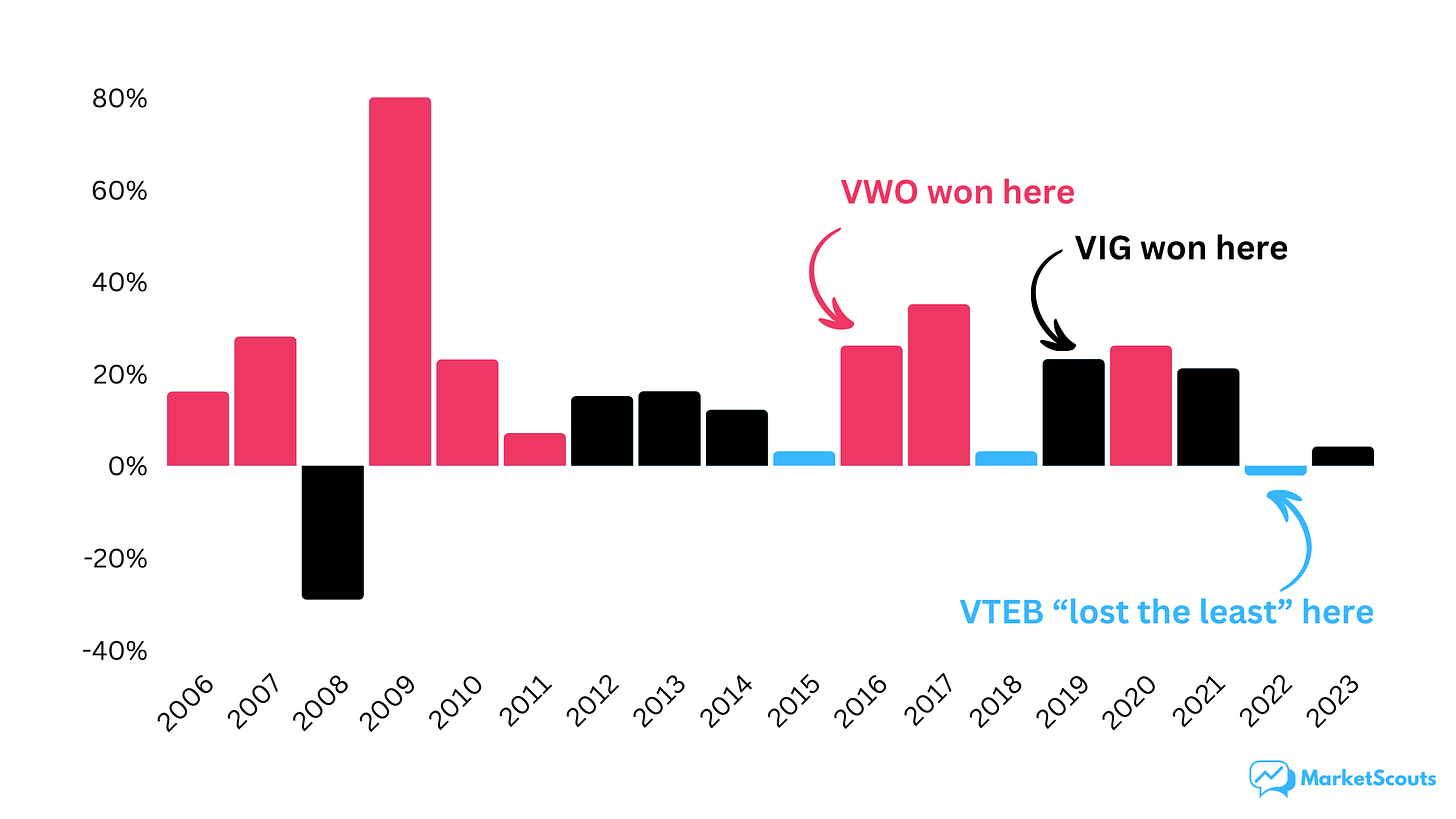

But what if we looked at the annual performance of each?

In other words, you’d invest at the beginning of each January and sell at the end of each December:

It’s a bit hard to believe, but since 2015, each of the three options has “won” the exact same amount of times: 3 years each!

And before that, it was evenly split before VWO and VIG too (VTEB wasn’t available yet).

Nice charts, what’s the conclusion here?

the risk-return “advertised correlation” is not always there. World events can have a huge impact. You need to look at the broader picture when investing.

however, the size of the swings (the ups and downs) you can expect DO follow the “advertised” risk profile.

you need to be cautious when an ETF or robo-advisor says "risk" as they mean "short-term" volatility. The real risk is you'll get frightened and sell when you shouldn't.

Which brings us to the most important part of this post.

How to understand your risk appetite and improve your ability to “stomach” the ups and downs of the market

Remember that lower risk means lower returns. Not always, but often. VGI might have beaten VWO while being slightly less volatile, but VTEB never had a chance. If you’re not comfortable with high volatility, you’ll have to settle for lower, VTEB-style returns.

Don’t trust robo-advisors or ETF risk ranking tools blindly: something ranked “risk 5” isn’t a more “aggressive” choice than something ranked “risk 4”.

Also remember that the real risk is now knowing what you buy. The stock market is not a “magic money machine”. If you pick your own investments and do your own research, you’ll be far more likely to withstand volatility because you’ll know what you own.

Vizualize your goals: retirement, kids’ college fund, etc. if it means something to you, then hold on to it.

Keep an investing journal: see how you feel when the markets go down. Try an app like Journalytic, it can be really useful.

And hey, maybe also talk to a therapist, take a personality test, or try mindfulness meditation.

If we learned one thing about investing, is that most of the time the person keeping us from achieving our goals is ourselves.

Understand yourself, what you’re happy with, but also what you’re comfortable with.

And when you see titles like this…

…remember that you didn’t buy them for a reason – you would have probably sold for a loss a long time ago…