Buying a "country" or "thematic" index may not mean what you think

You're paying a price that’s higher than you think – for being sold something that’s not exactly what you think it is.

With the US market getting ready for a new all-time high despite rising interest rates and an indicator that signals a potential recession, it certainly is tempting to look at other opportunities and “buy the next decade’s growth story” (India?) or invest in a specific technology or theme.

The easiest way to do it is of course, by buying an index – a country index if you’re looking at a specific country, or a thematic index if you’re interested in a new technology. The challenge is that it might not give you the “exposure” that you were looking for.

So, how does an index work?

An index fund is a type of fund (most of the time an ETF) that runs a portfolio built to track the companies making up a financial market index, such as the Standard & Poor's 500 Index (S&P 500) for the US.

What does buying an index fund really entail? Well, when you purchase shares in an index fund, you're essentially buying a small piece of every company listed in that particular index.

That’s why when you’re looking at a specific country’s index, let’s say CAC 40 for France, it might be tempting to think that you’re buying a little slice of France’s corporate pie.

Same goes for technology: an “AI ETF” should focus only on companies that are working on magic AI technologies… right?

That’s not entirely false, but there's a catch you were probably not aware of.

Local companies, foreign revenues

Now, you might be thinking, "Great, my money is boosting the French economy with my CAC 40 shares." But the reality is a little more complicated.

Today's globalized world economy has blurred the lines when it comes to investing in a country's index. The simple fact is that many companies, especially the large ones included in these indexes, earn a big chunk of their revenues from abroad.

Take for example, the same CAC 40, which is often regarded as a French index. Yet, a staggering 84% of the revenues of the companies included in this index come from outside France.

If we dig a little, we can see that CAC 40 companies are extremely international (multinational). CAC 40 companies have over two-thirds of their business and employ over two-thirds of their workforce outside France. In fact, according to The Multinationals Observatory’s “CAC40: the true annual report, 2022 edition”:

Most historical pillars of the CAC40 index continued to reduce their workforce in France: Carrefour, Sanofi, Orange, Renault, BNP Paribas, Société Générale, etc.

The same is true for its European counterparts like the FTSE 100 (UK), DAX (Germany), AEX (Netherlands), and SMI (Switzerland), which also have a big percentage of non-domestic revenues:

FTSE100 has 75% non-British revenue

DAX has 81% non-German revenues

AEX has 91% non-Dutch revenues

and SMI has a staggering 93% non-Swiss revenues.

So if you’re French, your domestic investment doesn't feel so domestic any more.

But that's not all.

Many indexes, same companies?

Here's another twist in the tale.

A lot of overlap exists between different indexes. Some companies feature in multiple indexes, meaning if you're investing in different indexes, you might be buying the same stock more than once.

Take a simple example: let’s say you want to buy the S&P 500 because you believe in the US economy. But you also want to buy the Nasdaq 100 because you don’t want to miss out on the growth in technology stocks.

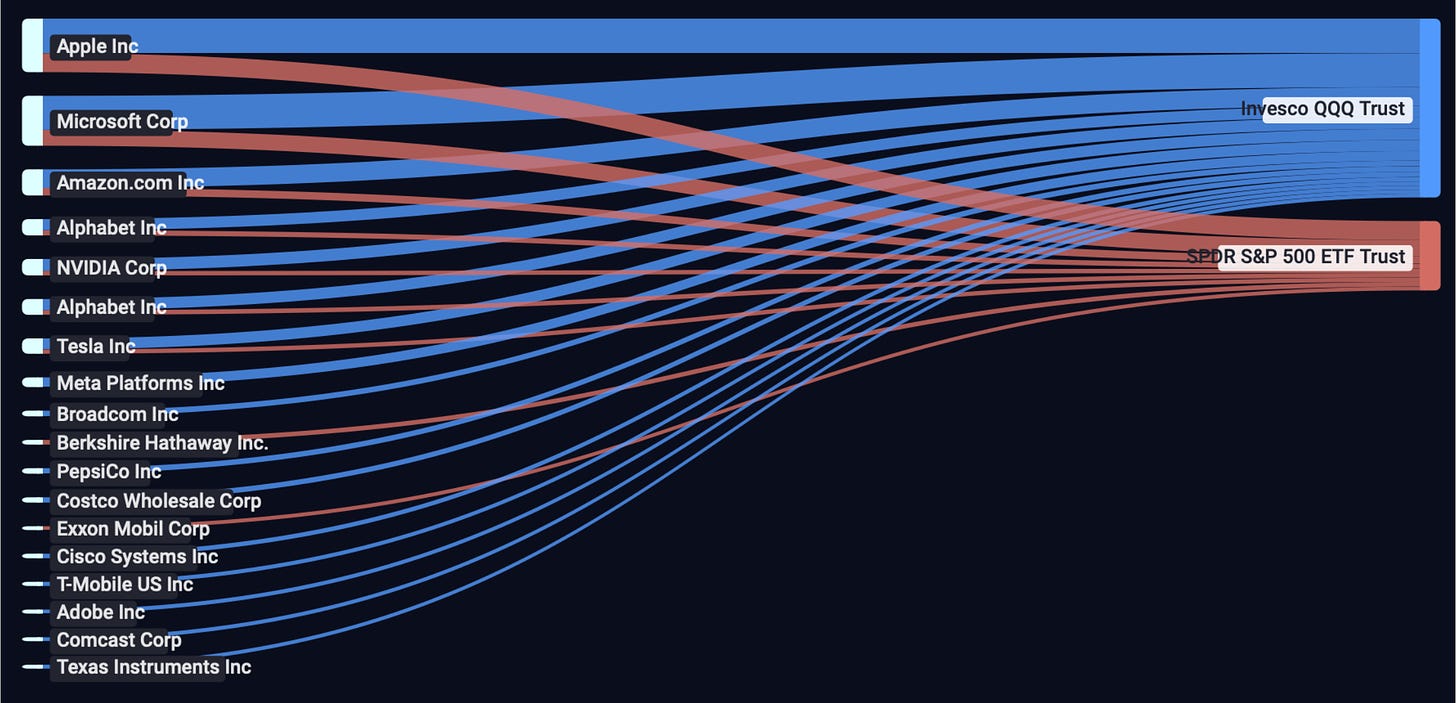

If you use a tool like ETFinsider to compare two ETFs tracking these indexes (SPDR S&P500 for, well, the S&P 500, and Invesco QQQ for Nasdaq 100), you’ll see that 16% of their stocks overlap.

It’s even worse if you look at a the overlap by weight, which you can check using a tool like ETF Research Center:

And this happens with many other indexes.

So much for easy diversification…

Now what?

So, what does this all mean for us, everyday investors?

First, it’s just good to remember that investing in a country’s index is really more like investing in the global revenue streams of the companies listed on that index. But that’s not the worst thing. Revenues earned by those companies do count towards that country’s GDP. So if you “believe in country X”, it really doesn’t matter where they get money from. In fact, investing in a country with strong exports or with large multinationals might be much better than investing in one too inward-focused.

Second, it’s good to dig deeper into a fund and see what you’re actually buying. If, say, your “diversified portfolio” actually has 40-50% invested in just a handful of companies, isn’t it a better idea for you to pick those stocks yourself?

What most people forget is that fees compound, too:

Is 7.71% in this example a good price to pay to buy something that you hope will “magically” make you money?

Maybe, maybe not. But it’s important for you to know that you are paying a price that’s higher than you think – for being sold something that’s not exactly what you think it is.