"Buy the rumor, sell the news". Meme or actual strategy?

"Buy the Rumor, Sell the News" is a strategy that's talked about a lot. But let's look at what a surprising study from Rutgers University has to say about it.

A few weeks back,

and I took a look at different market sentiment analysis tools. They were all quite interesting, but the real challenge is never what tools you have – it's how you use them.So, we decided to explore some sentiment-based strategies and see what data has to say about them.

We're kicking things off by checking out the “Buy the Rumor, Sell the News” (BRSN) strategy, which is talked about a lot:

Let's dig into it.

What is “Buy the Rumor, Sell the News”?

“Buy the Rumor, Sell the News” is a fairly simple trading strategy, in theory.

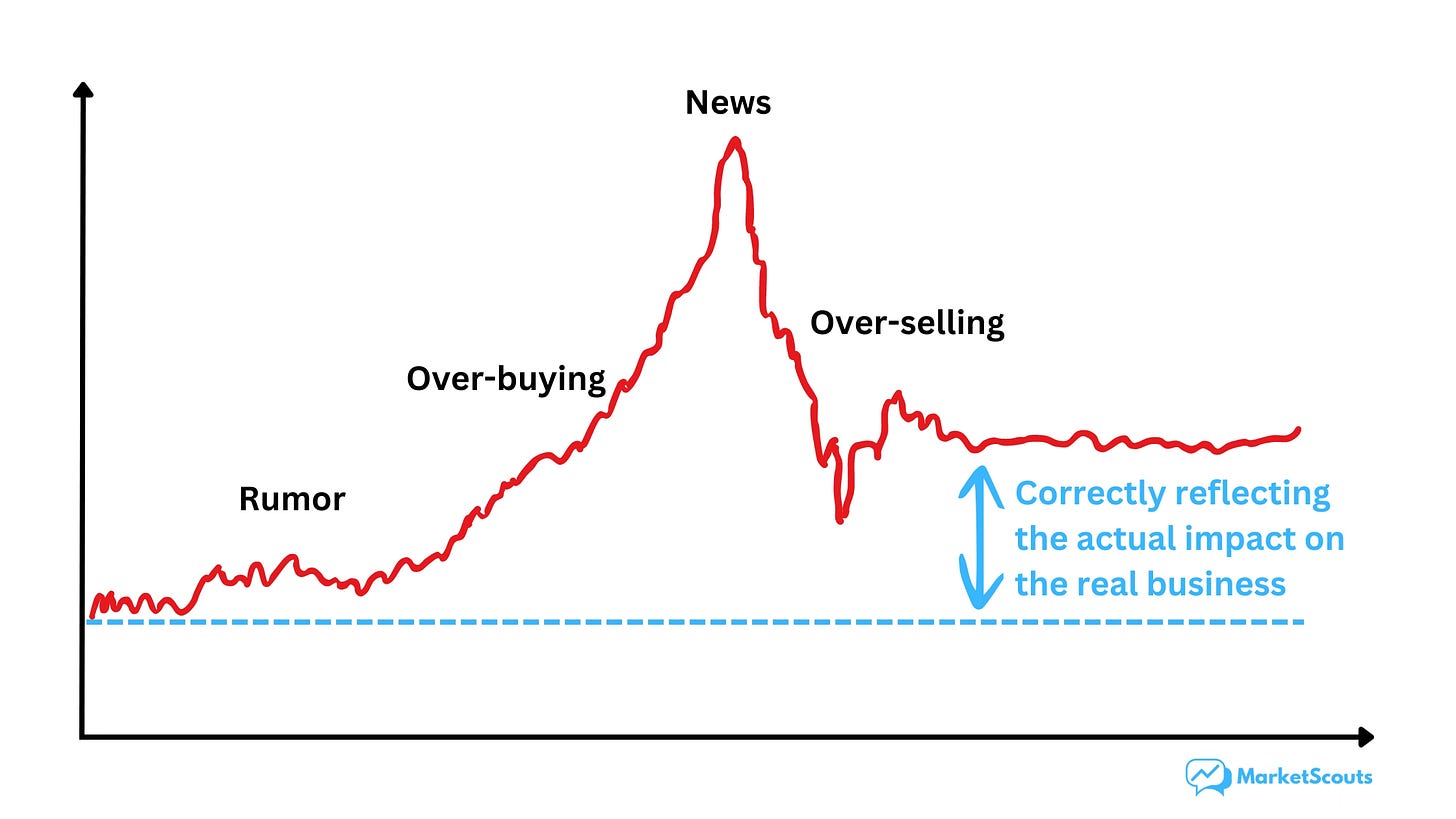

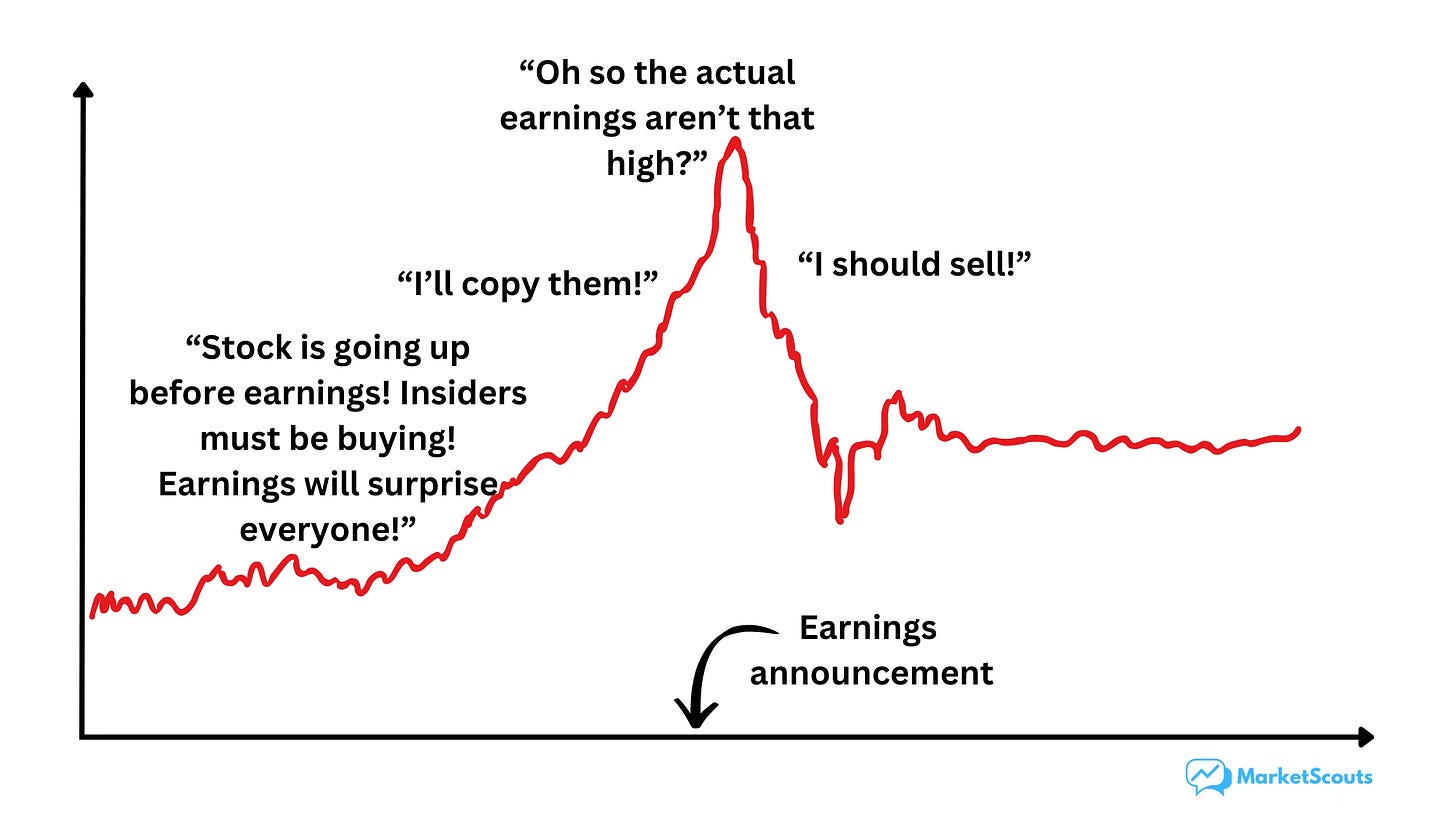

It starts with a rumor. This rumor might cause a stock to go up (or down if it's bad news), all in anticipation of an upcoming event, which we'll call the “news”.

When the actual event happens, the stock price has already factored it in. Those who bought in before the news now want to sell at the same time.

Sometimes that’s because the information is no longer fresh, other times it’s because once the news is confirmed everybody has a second look at what the actual impact it will have on the company’s business.

But if the majority of buyers piled in to the same rumor and is now looking to sell at the same time, the price will be impacted more than it should.

This leads to the stock price moving slowly up into the event, often overshooting, and then falling rapidly once the event occurs, and only later getting to a level that correctly reflects the real impact of the news itself on the underlying business.

What does the data say about “Buy the Rumor Sell the News”?

In 2016, two professors from the Rutgers University, Ivo Jansen and Andrei Nikiforov, published a study called “Fear and Greed: a Returns-Based Trading Strategy around Earnings”.

As part of the study, they looked at almost 700,000 (seven hundred thousand!) times when companies’ stock prices moved “abnormally” around their earnings announcements.

What do they mean by abnormal?

To understand their definition, keep in mind that companies announce their earnings four times a year. These announcements are usually the most important ones for investors. That’s when we get to see how much a company actually earned – or lost. Real news.

But until those earnings are announced, you don’t actually know anything measurably new. The market might respond to some macro news like interest rates, consumer surveys, etc., but in theory all stocks should respond to this info in a predictable way.

But obviously that’s not the case.

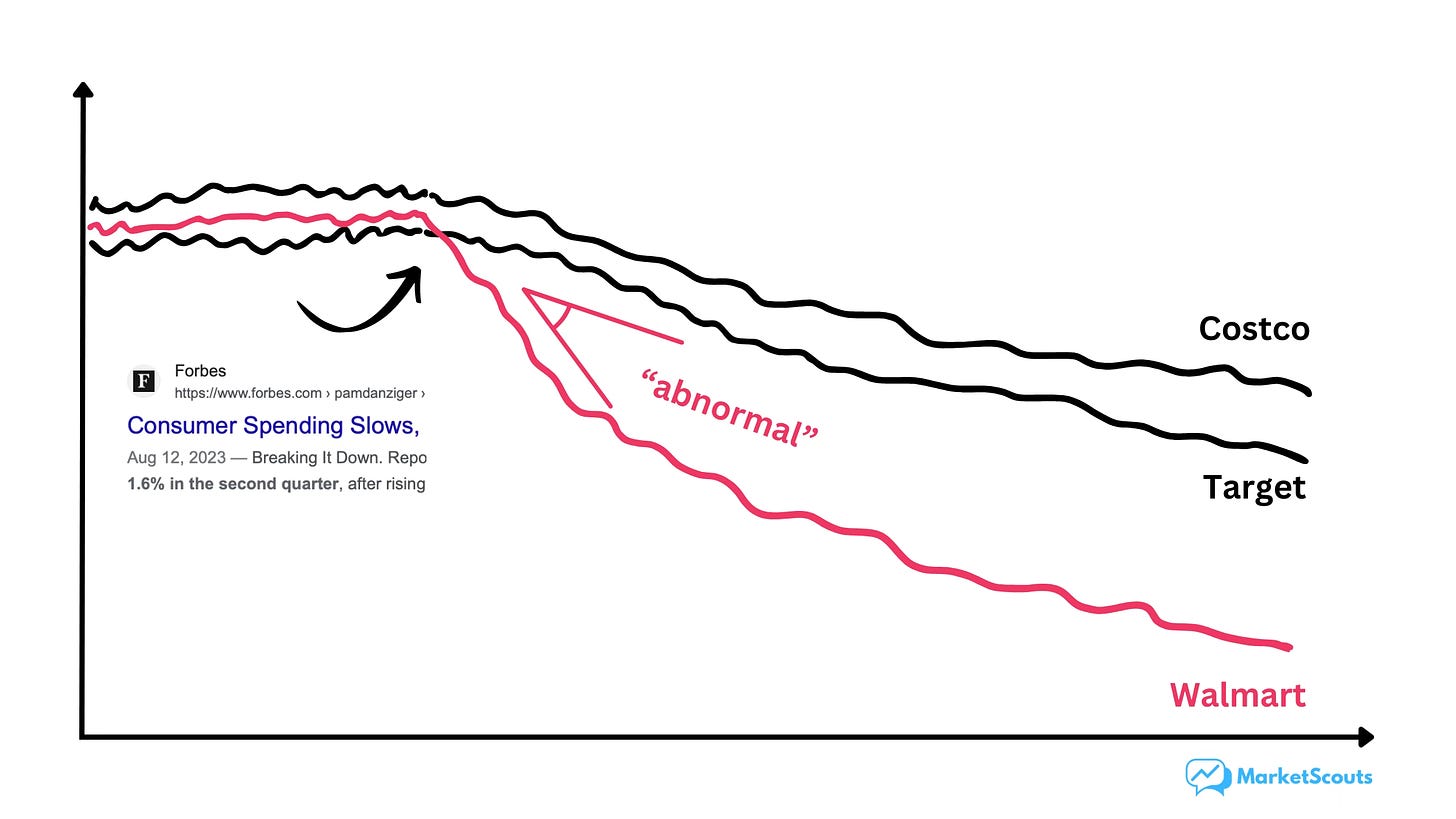

So Jansen and Nikiforov only shortlisted those price movements that are abnormal compared to the stock prices of similar companies.

For example, Target, Costco, and Walmart are retailers everyday products to consumers. And let’s say that a month after their Q1 earnings announcements – which cover earnings for January, February, and March – some surveys shows that consumers are feeling the pinch of inflation.

As a result, analysts will project that consumers will spend less that year. Bad news for all three retailers, which means that all three stocks should go down in a similar fashion.

But if Walmart starts to drop significantly more, then that’s… “abnormal”.

Looking at these so-called abnormal situations, Jansen and Nikiforov found a couple of interesting things:

First:

“Stocks with extreme abnormal returns in the week before an earnings announcement experience strong price reversal around the announcement.”

Their theory for why this happens is something like this:

uninformed investors (we?) observe sharp price changes just before an earnings announcement

we then may attribute these to the informed trading of insiders. If the stock price moves up, for example, we may believe that insiders know that the upcoming announcement will reveal unexpectedly good news.

greedy to profit, we start to “jump on board” and push the price in the same direction ourselves;

and thus cause an overreaction.

when the announcement happens it will serve as a reality check, resulting in a price reversal.

Next, Jansen and Nikiforov tried to implement a simple strategy: short the stocks that saw abnormal price increases before the annoucements. And buy stocks that saw abnormal price decreases.

The whole point being that, until the earnings are actually announced, there shouldn’t be any other news other than sentiment that explains the price movement.

Implementing this strategy, they found out that:

“Our strategy (1) is profitable in 40 of the 42 years in our sample; (2) is similarly profitable in “bear” and “bull” markets; (3) and is significantly profitable for both large firms and high volume stocks.

Since the year 2000—using a conservative transactions costs estimate of 70 basis points for a round trip trade—we find that our strategy generates abnormal returns of 0.76% after transaction costs, or 95% on an annualized basis.”

Basically:

a buy the rumor sell the news strategy focused on earnings calls performs consistently,

for all kinds of stocks,

in all kinds of markets,

and even while accounting for rather high trading costs.

Those are some pretty juicy results! Not surprisingly, Jansen and Nikiforov are pretty smug about it:

“This finding compares very favorably with the profitability of most well-known trading strategies, which earn positive returns in bull markets, but which tend to earn negative returns in bear markets.

To our knowledge, there is no anomaly or other trading strategy—including post-earnings announcement drift—that has been consistently profitable for such a long time.”

How to implement “Buy the Rumor, Sell the News” according to this study

If you’re interested in trying this strategy out, the authors have a few pieces of advice.

First, stay focused on earnings announcement dates.

“These return reversals are about 60% larger than around non-earnings announcement dates”

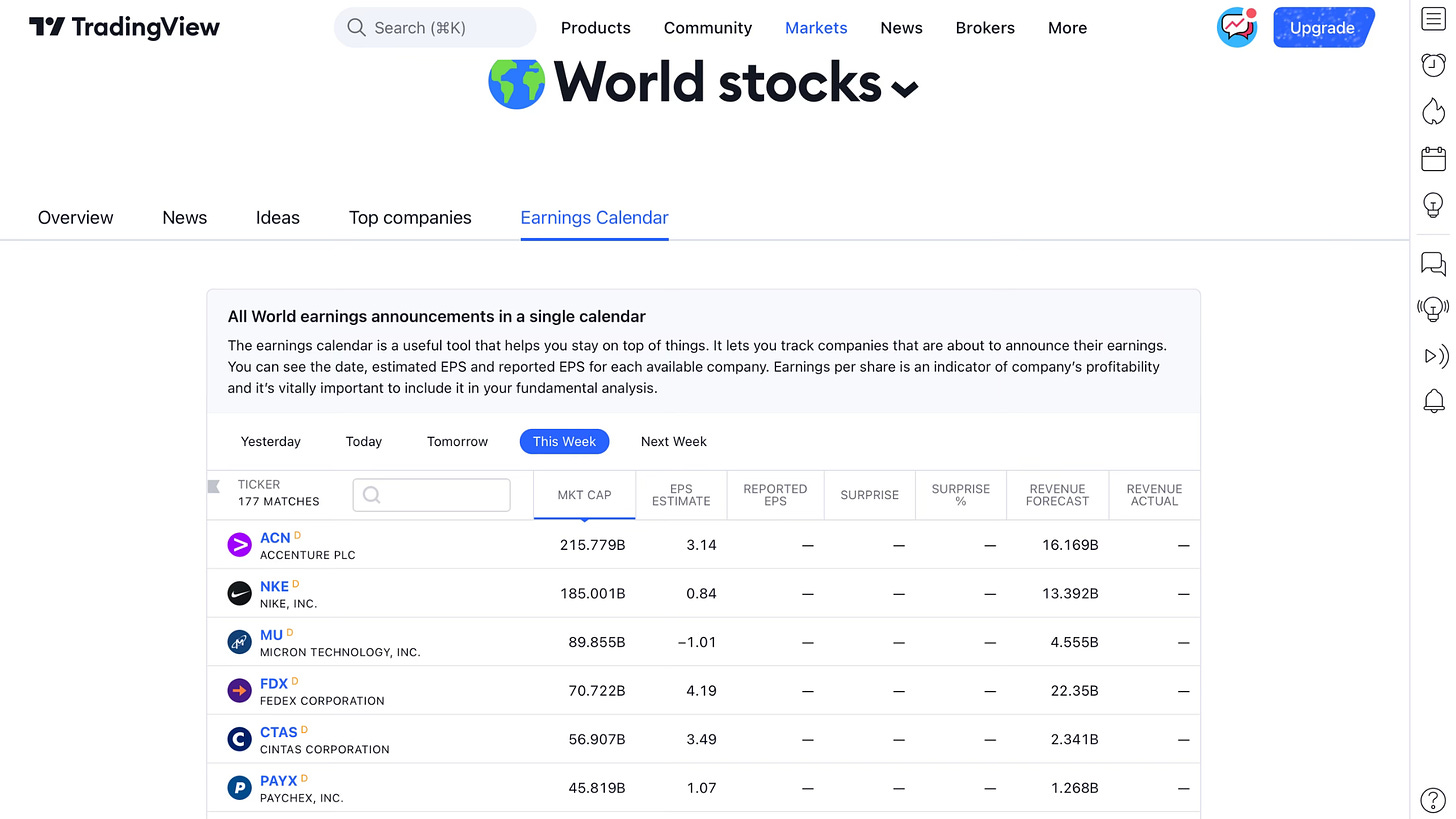

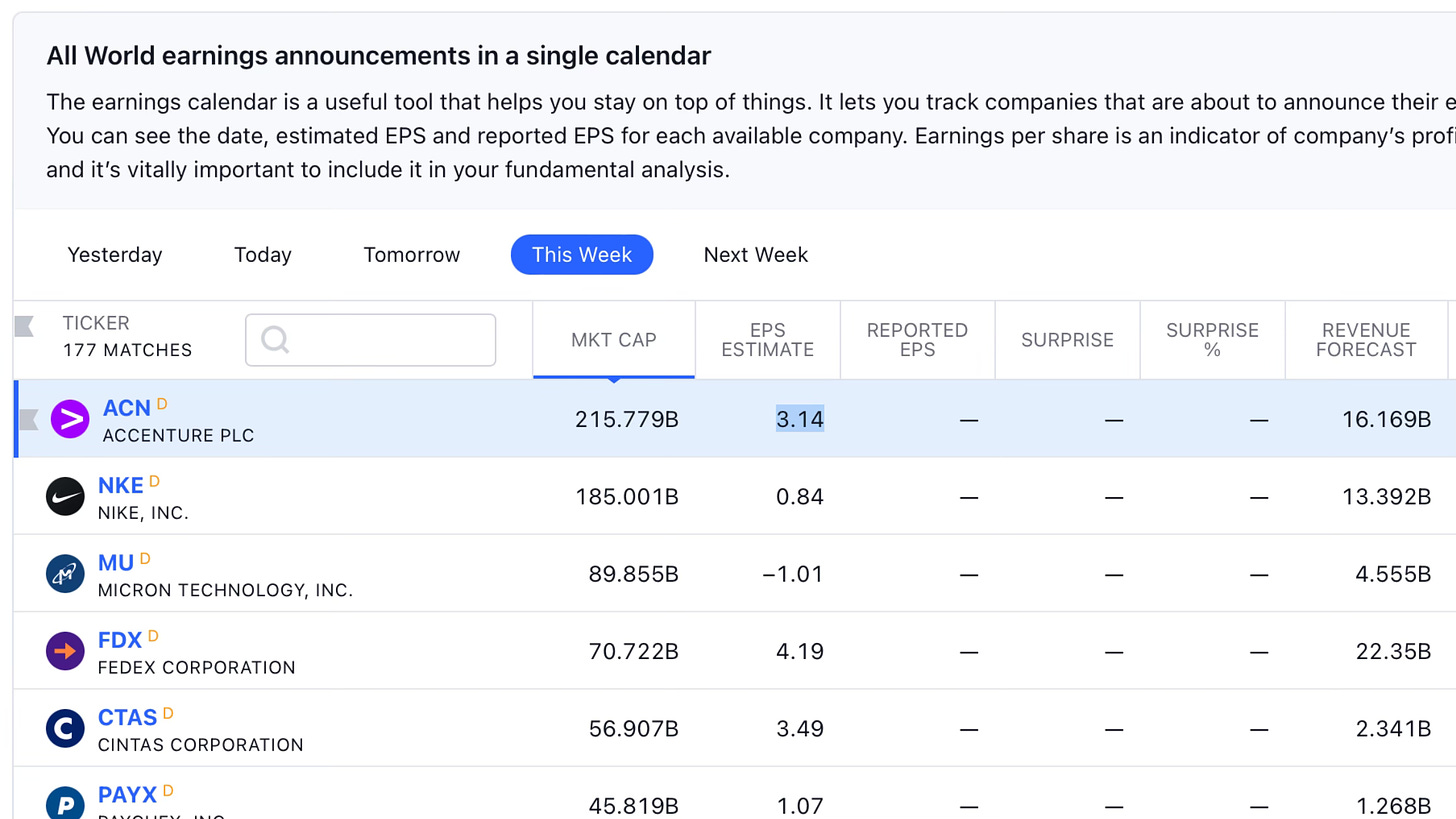

You can find upcoming earnings announcements on many websites. We recommend TradingView’s earnings calendar because you can easily filter out the markets that interest you.

Second, screen stocks five days but not later than two days before the announcement date.

“We do so to allow for the possibility that inside information leakage on the day immediately before the earnings announcement already causes return reversal at that time.

The results indicate that this is the case. Using a (-5,-2) screen, and a (-1,1) holding window, significantly increases the strategy’s profitability: from 1.49% to 2.36% for the long, and from 1.20% to 1.59% for the short position.”

But don’t start your screen too early.

“When we extend the screen window to start on day -7, -10 or -20, instead of on day -5, we find that the trading strategy becomes less profitable the further we extend the screen window.”

Now, this is where it gets a bit tricky. We couldn’t find a tool that does it automatically but we’ll keep at it. We’re also considering building a custom screener for this – stay tuned.

For now, we suggest two things:

use TradingView’s screener and then quickly compare each stock to 2-3 similar ones, and see how the price moved

look at the “estimates” for earnings, and compare that to the price move.

For example, Accenture is announcing their 2023 Q3 earnings tomorrow. The analyst consensus is that Accenture will announce $16.18 billion for their quarterly revenue and $3.15 for their EPS (earnings per share).

These numbers are called Revenue and EPS estimates.

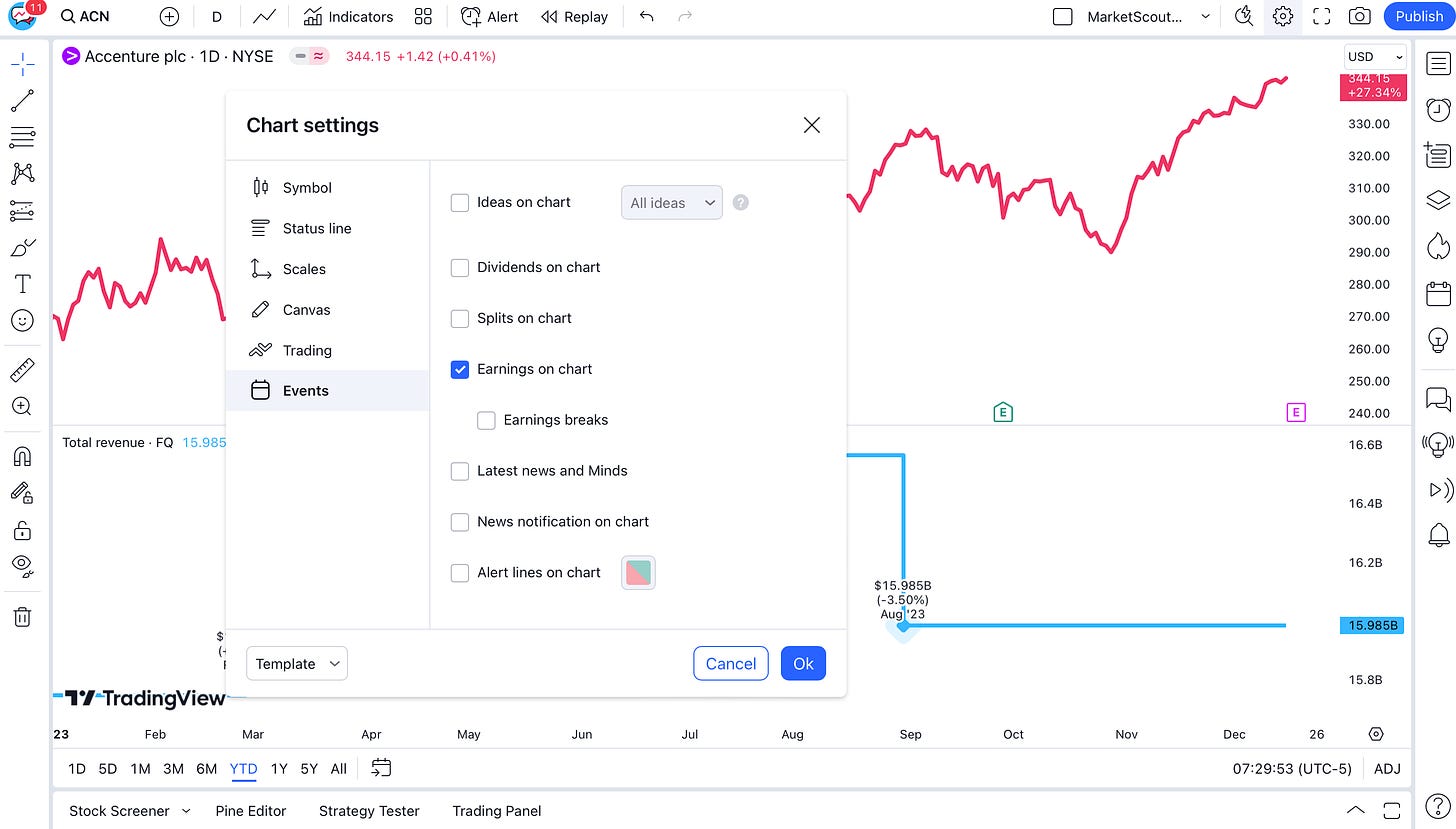

Their latest earnings announcement was on September 28th, which we can find by ticking “earnings on chart” in TradingView chart settings.

So let’s look at the price movement before then and now.

Again, in theory, there shouldn’t be too much of a price change – we don’t know anything new and material about the company. The price change should, if anything, be somewhat similar to the change between last EPS and the EPS estimate.

Since the last earnings call until now, the price has moved up almost 15.8%. But the EPS estimate for Q3 is actually quite a bit higher, at 44%.

We’re not saying that Accenture is underpriced. It might be.

It also looks fairly priced, in some ways – investors are basically taking the EPS estimate with a pinch of salt, which makes sense.

But to know more, you would need to look at its peer companies. Its direct competitors. And maybe also consider which analysts contributed to the EPS estimates and their track record.

Third, keep your position only for a short while, between one to five days.

“We find that the trading strategy becomes slightly more profitable when extending the holding window up to date +5.”

But not longer than that:

“However, we also find that further extending the holding window to day +10, decreases profitability.”

Basically, if you think that Accenture is underpriced in the example above, you would sell the stock, no matter what, one to five days after the announcement.

So between December 20th to December 24th.

Right on time for Christmas. 🎄

What next?

Please don’t buy Accenture or some other stock based solely on this study and those screenshots. We only looked into it for a few minutes because its earnings call is happening tomorrow.

If you want to pursue a “Buy the Rumor, Sell the News” trading strategy, you have to accept a few things.

First, it’s a highly risky strategy. You need to find truly mispriced stocks.

That doesn’t happen all the time. In fact, Jansen and Nikiforov quote other studies which show that, at the time of an earnings announcement, stock prices move in the same direction as the earnings surprise.

Second, this study was published in 2016. The hedge fund industry manages $4.5 trillion (with a T) worldwide. That’s a lot of money at stake. Consider that one in four hedge funds applies quantitative strategies like the one in this study.

They’ve had plenty of time and plenty of incentive to “squeeze all the juice” out of this research in a way that makes it much less profitable for you, today, seven years later.

Finally, if BRSN is your main strategy, then you need to trade a lot, and trade often. Do you really have time for it? Honestly, we don’t.

The way we plan to implement this strategy for ourselves is to use it as another filter in our stock screening process. Maybe trade a bit around some truly abnormal situations.

But we won’t follow every earnings announcement.

And probably neither should you.

“Buy the rumor, sell the news” is something we’ve seen all the time, especially on finance TikTok and Twitter. Despite this, we’ve only used it successfully a handful of times. Last time was during the SPAC craze of 2021 – a story for another time.

Meanwhile, we would love to hear your stories. Have you ever bought the rumor and sold the news successfully? Or lost in spectacular fashion?